Krisenmanagement: eine Frage der Demut

Valeria von Miller

Valeria von Miller

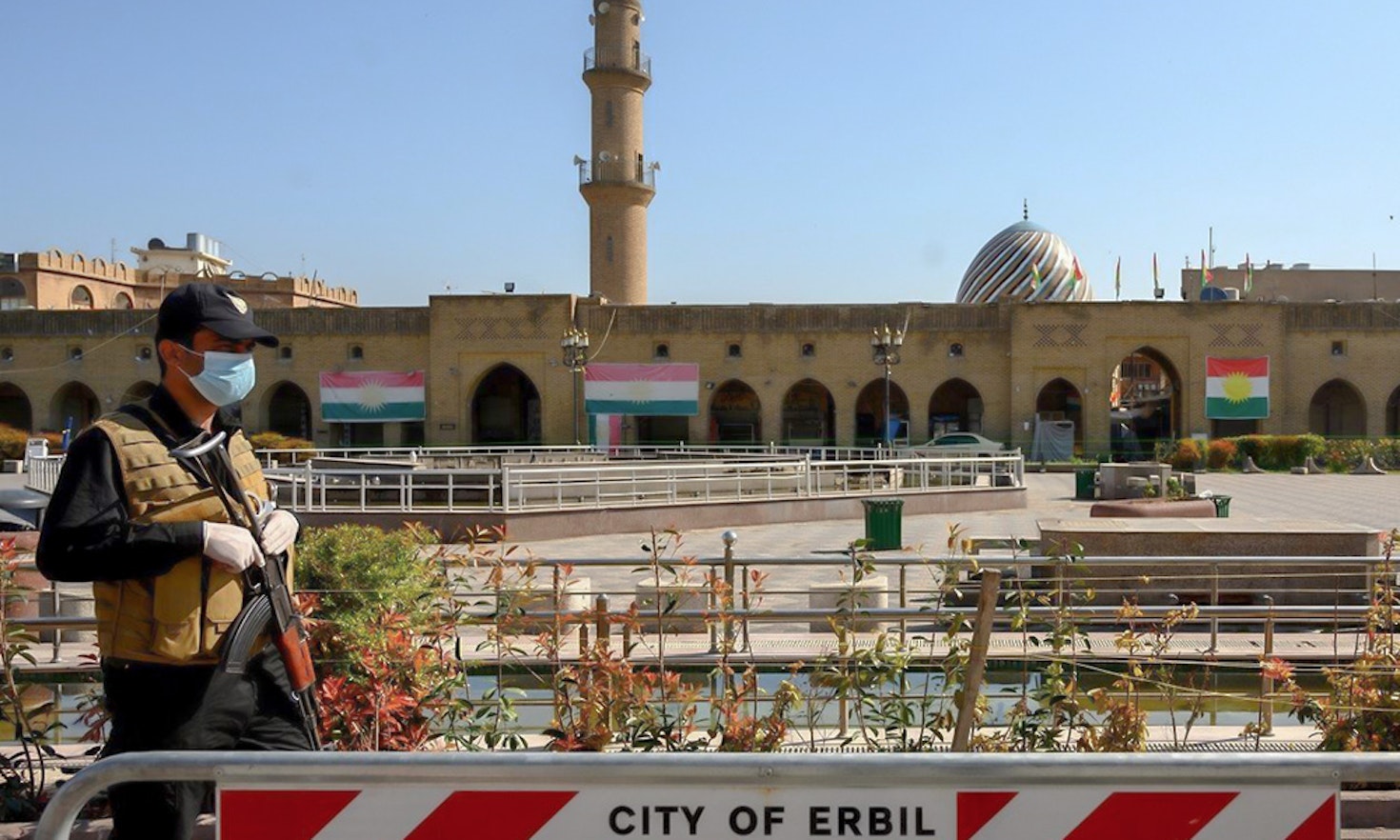

On 13 March, at the outbreak of the pandemic in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), the government responded in an authoritarian style through total lockdown, enforced curfew, quarantining returnees, and social distancing. A travel ban was also imposed between the provinces and the airport closed. There was a gradual closure of schools, universities and other large public gatherings, including public events, and major religious gatherings were banned. The KRI established a crisis committee, a hotline phone number and a website to respond to this unprecedented situation. The KRI is not a state, but a semi-independent constitutional entity within the federal State of Iraq. It comprises four governorates in the north: Erbil, Sulaimaniya, Halabja and Duhok, with a multi-religious population of around five million, including Muslims, Christians and Yazidis. It borders Syria to the west, Iran to the east, and Turkey to the north.

As of July, 2020, there have been 10,114 confirmed cases, 5,482 of whom have recovered, 370 died, 4,262 active and 238 new cases. During the first two months (March and April) of the outbreak, almost no cases were registered, mainly due to the enforced curfews ordered by the government. The securitised approach by the KRI government was necessary because it was able to keep the cases in the region very low. This response gained international recognition, as the World Health Organisation (WHO) praised the KRI authorities for its anti-coronavirus efforts and pointed to the stark contrast between the relatively small number of known infections in the KRI compared with the rest of Iraq, and neighbouring countries such as Iran and Turkey. However, this securitisation response created a great level of uncertainty in the community, and it has led to implications which may have long-term consequences. For example, the containment measures resulted in mass demonstrations and strikes were conducted by both public and civil servants.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) generally has bigger fish to fry in three key areas. Economically, since 2014, the government has been unable to provide full salaries for its civil servants and it is virtually bankrupt, and the Prime Minister recently announced that government debt is $27 bn. Since the region depends almost entirely on fossil fuel revenues, oil prices have gradually decreased, and indeed some have argued that the oil price drop has had a bigger knock on effect than the virus in the region. In consequence, the government is struggling to procure the personal protective equipment (PPE) products to cover the requirements forecast for the Covid-19 response.

The latest statistics released by Iraq’s Ministry of Planning show that the rate of poverty in the KRI is 5.5 % lower than the rest of Iraq, at 20 %. However, as well as not fully paying public servants, the government has not supported those on zero hours contracts who have been greatly affected by the pandemic, such as daily labourers and farmers. In recent times, as the prices for their products plummeted drastically, farmers have poured value-depleted harvested tomatoes and cucumbers into the streets of the capital city. Some argue that the government’s aggressive security measures and curfews were not imposed to control Covid-19, but to restrict freedom of movement and demonstrations.

In addition to these troubles, the region suffers from corruption, and although it is much less than in the rest of Iraq, it is still relatively high in comparison to other countries in the region. Two main political parties (the PDK and PUK) have established a political system based on nepotism, weak bureaucracy, and the mismanagement of oil revenues. In January, the Kurdistan Parliament passed a Reform Law to eliminate corruption in the public sector. The implementation phase of this law has only just started, and, therefore, one has to reserve judgement on its impact on corruption in the region.

The KRI also faces security and terrorism issues, as the terrorist activities of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) have resurged with the withdrawal or suspension of the Global Coalition, and the enforced curfew orders by the Iraqi and Kurdish security forces. Indeed, ISIL has used this opportunity to increase terrorist attacks on villages. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) has warned that the re-emergence of ISIL will increase the flow of migration from Iraq to Europe, and predicted that the pandemic could embolden ISIL, leading to a resurgence of their activities in Iraq and Syria. This would, in turn, further fuel migration.

Some have argued that a securitised response was necessary since the health sector, both in Iraq and the KRI, is suffering from years of under investment, conflict and war, poor management, corruption, and the loss of healthcare professionals through emigration. This combination of crises has left the health services on the point of breakdown, and so clearly the sector is ill prepared to respond to such a pandemic. In fact, the head of the government’s medical laboratories in the province of Sulaimaniya, Mazin Fryad, noted that, ‘I have been infected with the Covid-19 virus, but due to lack of doctors and health staff, I am obliged to continue working’. To reinforce the point, Mohammed Qadir, spokesman for the Ministry of Health, warned that, ‘The number of coronavirus infections is increasing drastically’. Healthcare professionals have also warned that it is likely the number will continue to climb and fatalities are expected to continue to rise substantially. With healthcare in the KRI on the brink of breakdown, the further spread of the pandemic could lead to disaster in the region.

Covid-19 has brought many challenges, and this has added to the existing economic, security, and healthcare issues in the region. With the pandemic exposing the vulnerabilities and gaps in the public sector, the situation in the region’s healthcare is like a vehicle that has loaded six tonnes when it can only take two. This overload has created unbearable pressure, and the sector needs international support and funding to overcome the challenges it is facing. In addition, the broken trust between the public and government is in urgent need of repair. While the long-term consequences of Covid-19 remain to be seen, the KRI must first pass through a most difficult period before it will be able to alleviate the current dangers to its economy, security, and healthcare.

| Abdullah Omar Yassen is a lecturer in Public International Law and the Head of the Cultural Relations Unit in the International Office at Erbil Polytechnic University. He received his PhD in International Refugee Law at Newcastle University, his LLM with Merit, in Public International Law from the University of Leicester, a Postgraduate Diploma in International Law from the University of Nottingham, and an LL.B Law with Honours from the University of Derby. Dr. Yassen is an external legal expert in the field of international protection for the European Asylum Support Office (EASO), and Independent Monitoring Officer at SEEFAR/ Migrant Project. Dr. Yassen has published several papers in the field of forced migration, refugees, and minority rights, and has also participated in many national and international conferences, workshops and seminars. |

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license except for third-party materials or where otherwise noted.