Measuring biodiversity and ecological connectivity - the ability of animals to move around their environments, provides insights not only to the health of our surroundings but also our own. Maps drawn up by an international research team show how much freedom of movement wildlife has in the Dinaric Alps - from Albania to the Karst - and how this movement can be encouraged.

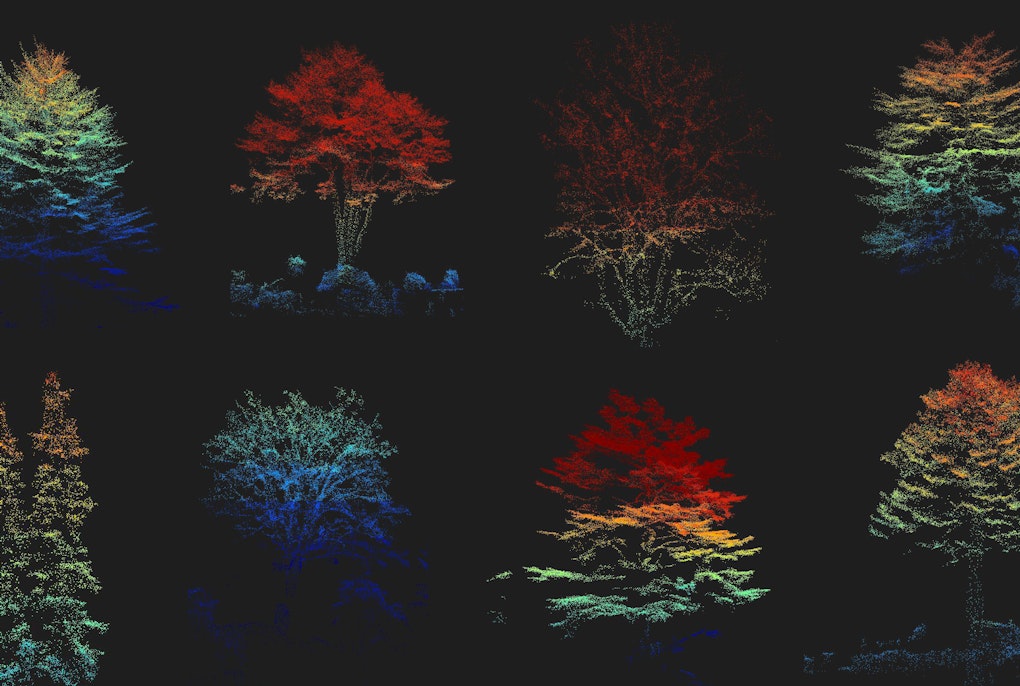

"If the bees disappeared, human beings would only have four years to live”. While the authorship of this phrase attributed to Einstein is doubtful, the message it carries is certain. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), more than 40 percent of invertebrate species, in particular bees and butterflies, are at risk of disappearing. Without them, many plant species would become extinct: domestic and wild bees are responsible for about 70 percent of the pollination of all plant species on the planet and provide about 35 percent of global food production. "The example of bees is particularly apt, but it can be applied to other animal species. Healthy nature allows people to live healthy lives," explains Filippo Favilli, a geographer at Eurac Research who studies how people adapt to the environment and its changes. "Human activities strongly modify natural environments, endangering the proper functioning of ecosystems and consequently the well-being of humans themselves." Biodiversity and connectivity are the keys to keeping nature healthy. And it is precisely on connectivity - the ability of wildlife to move freely in their environment and find spaces to reproduce, feed, rest and protect themselves - that an international research team has mapped the Dinaric Alps. Using Geographical Information Systems (GIS), the researchers have reconstructed an ecological network across the project area, from South Tyrol to Greece, identifying the most important areas to protect and the connections between them while at the same time, integrating human presence into the development of local action plans in the four pilot areas on the borders between Greece and Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia, Croatia and Slovenia, and Slovenia and Italy.

"We are faced with two types of barriers: physical and administrative. The former - which can be motorways, railways or cities - prevent animals from finding their habitat and put them at risk if they try to cross them, as well as posing the potential risk of road accidents. Administrative barriers, on the other hand, are boundaries drawn on a map: they don't actually hinder the movement of animals, but they still need to be addressed at an institutional level," says Favilli. To prevent ecosystems from fragmenting further and to improve ecological connectivity across the region, a common strategy is needed to coordinate infrastructure development, manage urbanization and define national agricultural and forestry policies. Some areas of NATURA 2000, the European network of protected nature reserves, are located on the border between two states. The aim of the DINALPCONNECT project is to strengthen cooperation within the Dinaric mountain range and to foster links within the Alps. The research team collected spatial data to analyze the current state of ecological connectivity and identify corridors and barriers.

Peter Laner, researcher at Eurac Research, gives an overview: "In Italy, intensive land use and settlements on the valley floor are two of the most important barriers. The Adige Valley, to take a local example, continues to be an insurmountable barrier to wildlife. In Slovenia and eastern Croatia, lowland areas have a highly fragmented landscape and highly developed land use, whilst mountainous areas are generally more protected. In Montenegro and Albania, it is the coastal areas that are most impacted and in turn exploited by human activities.

In general, the research team highlighted that the area of protected areas outside the European Union - despite their naturalistic value - is much smaller than in the member states themselves. Moreover, more than a third of all protected areas do not play a particularly useful role in wildlife connectivity.

"Across the whole area considered, the GIS approach identified 60 intersections between highways and potential green corridors. This is a mathematical model, so it is important that the results are verified in the field to check whether the motorways really are a barrier or whether there are other crossing options, such as tunnels or subways," Laner continues. This information, translated into maps, can help politicians and local actors to adopt common strategies for safeguarding ecosystems. In a series of meetings, each of the project's pilot areas involved relevant administrators and stakeholders - farmers, tour operators, hunters, breeders.

In the pilot area on the Slovenian-Croatian border, for example, the focus was on maintaining pastures because they are an important habitat for various wild species and serve to limit the natural expansion of forests towards land that is no longer cultivated. Local actors identified the most important pastures to be protected and, together with farmers, carried out restorative actions. "Having direct approach on the ground is essential to convey the biological value of these areas," concludes Favilli.