The Atlas: A new tool for mapping and measuring religious or belief minority rights

Silvio Ferrari

Silvio Ferrari

Very often, the opening of reception centres in rural areas depends on superordinate political levels. How do mayors in rural areas react to this decision? In our research, we interviewed mayors from Austria, France, Germany, and Italy and identified five commonly used strategies.

“On Tuesday they (note: regional gov.) told me there will be no accommodation in our municipality (…) on Thursday, I received a phone call at 10am, that there will be two busses of asylum seekers arriving at 2pm”.

(German mayor)

In the everyday politics of small rural municipalities, the topics of immigration and asylum are treated superficially. In general, migration to rural areas is low compared to cities, and rurality is often imagined as a homogeneous and quiet cultural space.

In our research, we interviewed mayors in Austria, France, Germany, and Italy. All selected municipalities have less than five thousand inhabitants, a population density below 300 inhabitants/km² and usually no prior experience with asylum and immigration policies. The opening of an accommodation centre is subject to superordinated political levels, such as regional and national governments, who establish direct contracts with service providers.

Local inhabitants often react with reservation and anxiety to this involuntary process, as people fear that this will impact the life in the municipality. In fact, in many European countries’ mayors have little to no say regarding the decision on the opening of an accommodation centre. We were thus interested in the role of the mayor in this process and the vertical and horizontal negotiation that come along with it. In our research, we wanted to find out whether mechanisms were alike regardless of the national context.

Rural mayors and the lack of decision-making powers

Considering the uneven decision-making powers rural mayors face, they must make an effort to accommodate the interests of the local citizens and manage the requirements of the subordinate political level. While some mayors were informed before-hand or even anticipated the opening of an accommodation centre that belongs to the community, others were taken by surprise and could only react by attenuating the situation.

Although it is hardly possible to reverse to overall decision of the opening an accommodation centre, mayors were quite successful in altering the terms and circumstances of its implementation. Contrary to its city counterparts, mayors in small-scale municipalities are directly affected by changes in the community not only as politicians and representatives of the municipality but also as inhabitants and citizens. As such, mayors usually are the first contact person and are held responsible for events that are happening in the municipality regardless of their factual decision-making powers.

How do rural mayors handle vertical and horizontal conflicts?

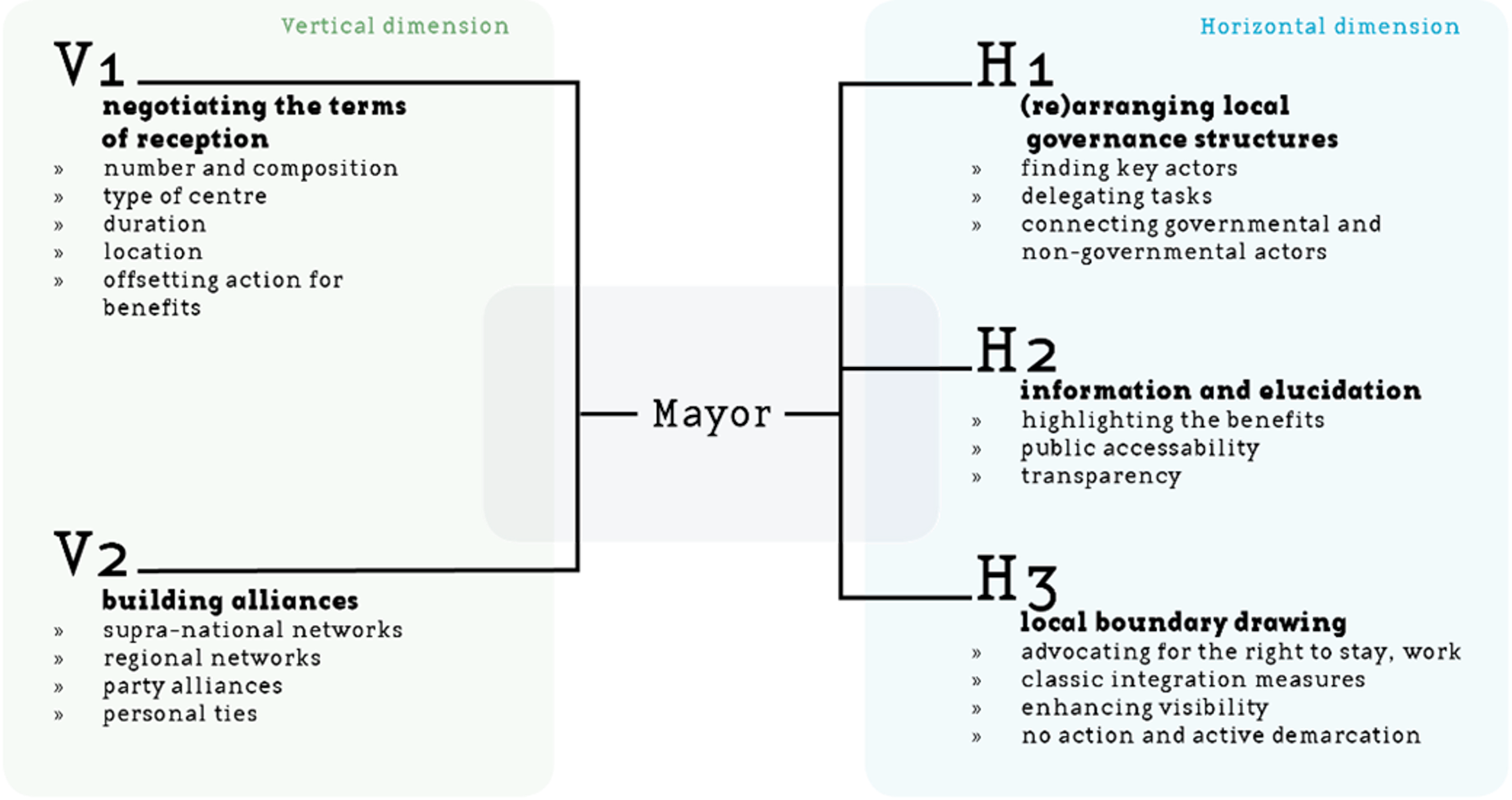

The figure below illustrates how rural mayors have developed five strategies to diffuse conflict and increase acceptance. Two of them are directed toward the vertical level, e.g., the regional, the state and/or the national level, and three are directed towards the horizontal level, which are inhabitants of the municipality.

Photo: Miriam Haselbacher, Helena Segarra | All rights reserved

Photo: Miriam Haselbacher, Helena Segarra | All rights reservedOn the vertical level, mayors engaged in negotiations with the superordinated political level upon the number of refugees and their composition in the accommodation centre (e.g., families). Certain mayors anticipated the opening or took a proactive stance, in providing municipal infrastructure, to gain control over the reception process.

Retrospectively it was the right way to look for a partner who assumes the supervision of the unaccompanied minors and to make the municipality owner of the property. … Once it belongs to the public administration, it is possible to control it and to consider the preferences of the citizens, a private investor from the outside would not have cared.

(German Mayor)

On the other hand, the mayors decided to build alliances and made use of their networks. Here, it was either personal ties to people belonging to the same political party or to people from superordinate administration that helped mayors to meet their wishes. As an alternative, they established new networks and alliances based on the shared feeling of grievance over being left alone. Negotiations on the horizontal level, however, were more comprehensive. This can be explained by the characteristics of local policymaking in small-scale environments, namely proximity and direct concern, the lack of infrastructure and the mayors’ own interests in maintaining power. Mayors thus rearranged local governance structures, delegated tasks and identified key actors in order to assume a monitoring role without losing access to information. They engaged in a process of direct communication with citizens to explain the reception process, obligations and circumstances, and highlight positive effects.

“This created two jobs in the municipality, and here employment is scarce and with the children we could save one school class from closing down, and those people use the post office, the pharmacy, associative activities, which is important in rural areas.”

(French Mayor)

“I did all the communication myself, externally and internally, with my local citizens, always the latest news, what was happening in the municipality. They needed to know that they were taken care of because I did not cause this situation, I could only react, otherwise I would not have a chance. And that was my part in it.”

(Austrian Mayor)

The most used strategy was local boundary drawing as mayors played a decisive role in governing the inclusion/exclusion of refugees within the municipality. Measures ranged from inclusionary actions such as campaigning for a right to stay and finding employment to no specific action that generally ends in ignorance a co-existence with little or no contact and exchange.

When the first people arrived, we organized a get-together at the town hall to welcome the people and let them meet the locals. There was some motivation, and then, after six months, people started to leave and others arrived and we had to start all over again … and now people are tired and the CADA is now in its own corner.

(French Mayor)

Politics of Adjustment

To comprehend these findings we have conceptualized the term Politics of Adjustment as a way of accommodating change that comprises two aspects: it is the process of people adapting to a new situation as well as the alteration of implementation practice by local actors. Why is that so? First, all strategies described above aim at establishing a local consensus to settle and resolve the situation as well as to (re)consolidate the power of the mayor. In view of the deprivation of decision-making authority regarding the overall decision to open an accommodation centre, rural mayors make use of legislative gaps and their administrative powers to adjust the framework conditions according to local preferences. The development of a local consensus is based on the alteration of reception conditions and the careful definition of local boundaries. Mayors thus successfully channel the hate and defuse resistances, but they also steer the socio-political process of demarcation and othering. This brings us to the second point: politics of adjustment target first and foremost the citizens of the municipality since mayors (re)act based on the preferences of their electorate and their personal beliefs. The implication of this, is that the voices and interests of refugees remain marginalized.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Silvio Ferrari

Silvio Ferrari

Stefanie Doebler

Stefanie Doebler

Leiza Brumat

Leiza Brumat