Indigenous Mobility, Urbanization and Participation in Latin America

Ilaria Signori

Ilaria Signori

How can a diasporic community build a collective identity in our modern era of nation-states, and how do nation-states respond to them? The case of the Pontian Greeks provides a little-known, yet relevant answer to these existential questions. In 1923, Pontian Greeks were forcefully displaced from the southern shores of the Black Sea, where their community had lived since Antiquity, to Greece. Since then, Pontian Greeks have been imposed a narrative of victimhood. This narrative actively serves modern-day Greece, as it feeds into the country’s longstanding disputes with neighboring Turkey. This complex, nuanced case study exemplifies to what extent the identities of minority groups can be manipulated, if not weaponized, to serve the broader geopolitical interest of nation-states.

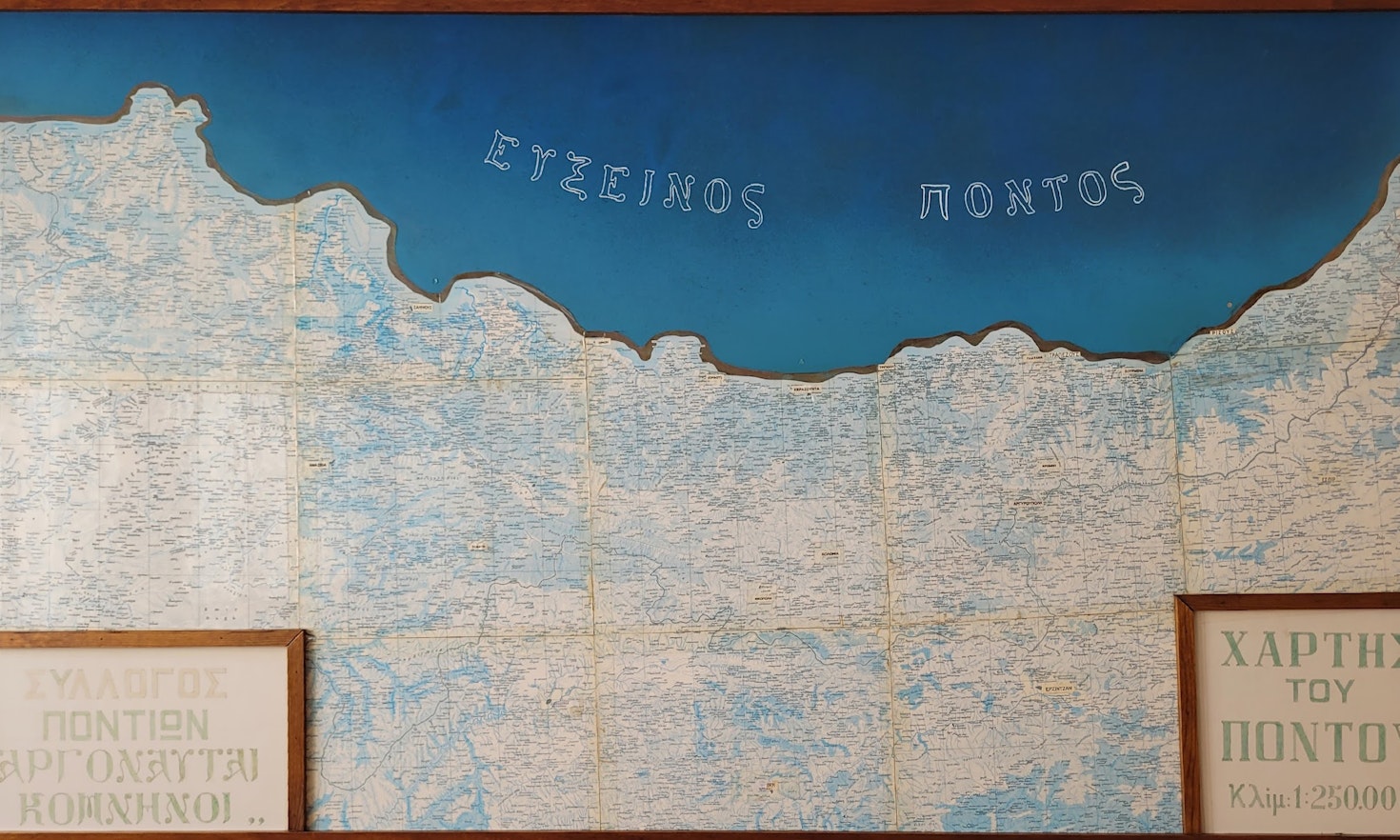

Between the eighth and sixth centuries B.C., a colony of Greek merchants and sailors left mainland Greece to settle on the northeastern coast of Asia Minor, on the shores of the Black Sea, in a territory they baptized “Πόντος” (“Pontos”), meaning “sea.”

For over 2,500 years, the Pontian Greeks developed their identity in symbiosis with the territory and peoples surrounding them, and themselves had a powerful influence on their surroundings. For instance, in the fourth century B.C., the Kingdom of Pontos was founded by a Persian dynasty that gradually developed strong Hellenic characteristics. By the second century B.C., the Kingdom of Pontos’s official language was Greek.

The Pontians’ ability to maintain their own distinct identity amidst different empires is also evident following the conquest of the Ottomans - a Muslim Turkic empire - in the 15th century. Pontian Greeks henceforth fell under the administration of a Greek orthodox leadership. From the distant capital of Constantinople, this leadership administered over a diverse Christian orthodox population spread across the vast Empire.

In the late eighteenth century, a budding Greek intelligentsia in mainland Greece and Constantinople developed a novel idea: all Greeks were the direct heirs to Ancient Greece. Greek nationalism, and the notion of Greek independence from Ottoman rule, spread in the first decades of the nineteenth century. A successfully organized insurrection led to the first constitution for an independent Greek state in 1822.

These developments had very little to do with the Pontian Greeks. Though sharing a common religion, Pontians had little in common with “mainland” Greeks, from whom they had been separated for nearly 2,500 years. They did not share the idea of a shared Greek identity rooted in Ancient Greece and the idea of a common state. They did not even speak the same language: though sharing the same roots in Ancient Greek, Pontian Greek, and the Greek spoken in the new Greek state were not mutually understandable.

In the 1910s and -20s, the presence of this unique population in the Pontos was brutally ended. Starting in 1913, the Ottoman government began forcefully deporting, assimilating and orchestrating massacres of the sizable Greek population living in the Empire. The landing of Greek troops in Smyrna in 1919 spurred a violent reaction from the Ottomans, sparking the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922). In 1922, Greece and the newly established Republic of Turkey orchestrated a dramatic population exchange on the basis of religious affiliation. Approximately 1.2 million Greek Orthodox peoples living in Turkey were forcibly relocated to Greece, while approximately 380,000 Muslims living in Greece were relocated to Turkey.

The survivors of nearly a decade of genocidal campaigns were forced to resettle in a territory their distant ancestors had left over 2,500 years earlier. Today, while approximately half a million Pontian Greeks remain in Greece, Pontian Greek communities today are also scattered in diaspora across the globe.

During my time in Athens, I uncovered a common popular narrative on the history of the Pontian Greeks. What I found, through visits to museums and interviews conducted with politicians and researchers, was a laser focus on the events of 1913-1923. This narrative contained three stereotypical actors: a villain (the Ottomans), a victim (the Pontian Greeks), and a victor (the modern Greek state).

Part of this narrative is certainly true. Ottoman authorities did conduct a genocide against the Greek orthodox community in the Ottoman Empire. By relocating to Greece, by permanently divorcing them from the territory to which they owed their name, and, indeed, their identity as a people, the modern Greek state essentially saved the Pontian Greeks from potential further genocidal campaigns. But is it the whole story?

Since the 1980s, Pontian Greek activists in Greek society have campaigned for the recognition of the Pontian Genocide. In 1994, the Greek parliament instituted Pontian Genocide Memorial Day. A smart move to garner enthusiasm from the sizable Pontian Greek community in Greece and ensure their support for the Greek state, it was also emblematic of the complex relationship between Greece and Turkey from the twentieth century to the present day.

Over the past century, Greco-Turkish relationships have been marked by military, diplomatic and territorial conflicts, the most well-known issues concerning Cyprus, the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, energy pipelines, migration and, naturally, minority rights. Throughout these conflicts, both have had a vested interest in painting the other as the perpetrator and themselves as blameless victims.

Both countries have difficulties publicly acknowledging the nuance of these complicated issues. So it goes, too, with the atrocities committed in the early 20th century. While Turkey today still does not recognize having conducted intentional genocide against Greeks and Pontian Greeks, Greece similarly does not recognize its complicity in the Balkan wars of 1912-13, during which unprecedented massacres were led against Muslim populations: over 200,000 Muslims left the Balkans as refugees, many of them settling in what was then still the Ottoman Empire.

Upon their arrival in Athens in 1923, Pontian Greeks rapidly adapted to Greek society. But did Greek society adapt to them? In Greece, there have never been schools or services offered in the Pontian Greek languages. Pontian Greeks were expected to learn the Greek language as it was spoken in Greece, which they did. Pontian Greek never had any official linguistic status in Greece. Today, it constitutes an endangered language, as it is spoken fluently by only a fraction of Pontian Greeks. In short, while, in 1923, the Greek government welcomed this population from the Pontos as fellow Greeks, they did not embrace their distinct identity as Pontian Greeks. This had serious consequences on the survival of so many elements that constituted the unique identity of Pontian Greek.

Today, the Pontian language, heritage and culture survives only because of the work the Pontian Greeks have done to preserve their identity. In a suburb of Athens, I had the opportunity to visit a Pontian community centre. Its aim, one of the volunteers told me, was to preserve Pontian identity by offering Pontian Greek language courses and theatre classes, as well as dance classes following Pontian traditions.

The case of Pontian Greek identity today highlights the major role played by nation-states in policing the identities of those we might consider “minority” groups. Stripped from their homeland, Pontian Greeks were resettled in mainland Greece where they were in no way encouraged to maintain their unique identity and heritage. The atrocities of the early twentieth century, which permanently altered their fate as a people, are well worth acknowledging and studying. It is, however, also worth recognizing how the modern Greek state benefits and draws from this victimhood narrative to feed into the country’s long-standing disputes with Turkey.

To define Pontian Greeks by their victimhood is doing them a huge disservice. The work of Pontian Greeks in Greece and across the world to maintain their unique identity as a diasporic community is testament to their remarkable resilience. Whether the Greek state wills to acknowledge this remains to be seen.

Disclaimer: In May 2022, I travelled to Athens to conduct field research on the history of the Pontian Greeks. As a historian of nationhood and identity formation, my research question was simple: what social, historical and political factors shaped the identity of this group who, in our era of nation-states, were not granted a nation of their own? This piece is a shortened version of a long form research essay previously published electronically. You can find this essay, with references, here.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Ilaria Signori

Ilaria Signori

Verena Wisthaler

Verena Wisthaler

Katharina Crepaz

Katharina Crepaz