How Frontex Frames Non-Rescue as Humanitarian

Eline Waerp

Eline Waerp

Immigrants partake much less in policy-making processes than persons without a migration biography. The obstacles they face result in a range of informal venues and forms of participation. The programme Land.Zuhause.Zukunft explored how immigrants can partake in decision-making processes at the local level, based on research conducted in eleven rural districts of Germany.

“As an immigrant, I also want to be part of decision-making processes in my region, in my town. For example, about who’ll become the mayor of my town, who’ll represent me on the town council.”

As illustrated by this quote from one of our interviewees, participation and representation of all members of society are crucial elements of any viable democracy. Participation enables individuals to communicate their interests and work towards adequate solutions. At the same time, it increases the legitimacy of outcomes. But immigrants partake much less in policy-making processes than persons without a migration biography. For instance, legal barriers prevent foreign nationals from voting in Germany. The obstacles immigrants face when attempting to (formally) participate in decision-making processes result in a range of informal venues and forms of participation. In a policy brief published as part of the programme Land.Zuhause.Zukunft, a co-operation with the Robert Bosch Foundation, we have conceptualised these forms and analysed empirical examples in eleven rural districts, all of which are or have been members of the programme. As such, these districts work towards finding innovative solutions to the challenges they encounter when supporting immigrants to become active members of their local communities.

“As an immigrant, I also want to be part of decision-making processes in my region, in my town. For example, about who’ll become the mayor of my town, who’ll represent me on the town council.”

Types of participation

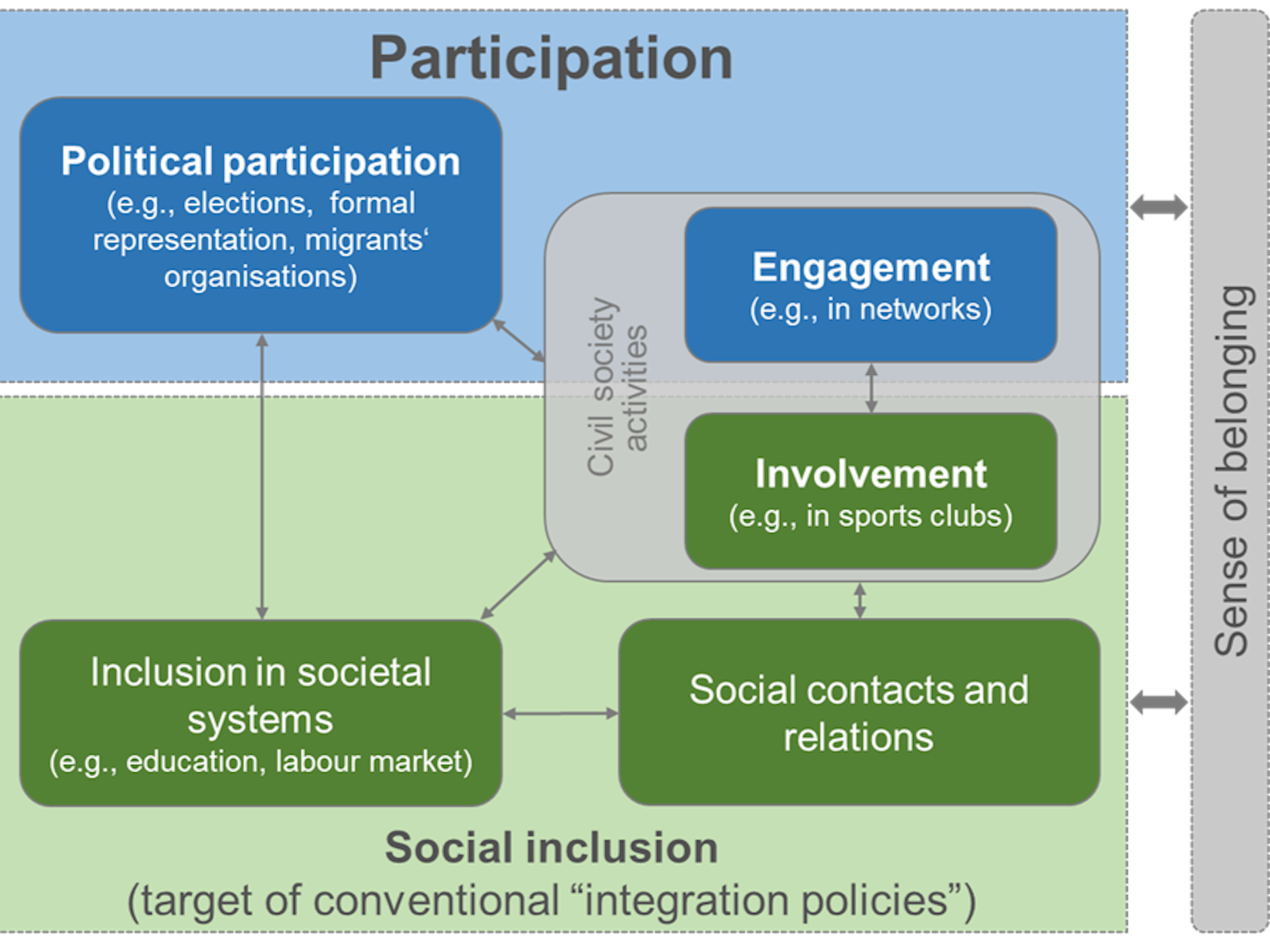

We identified two types of participation aiming to influence local processes and outcomes, as depicted in the diagram below. Firstly, “(political) participation” comprises those activities that are explicitly directed at decision-making processes, spanning from becoming a member of a political party or a “migration council”, or founding a migrant organisation to lobby for immigrants’ interests. Secondly, “engagement” refers to becoming active in a civil society organisation or network that aims to shape social, cultural or political issues.

Photo: Johanna C. Günther, Danielle Gluns, Julia Lisa Gramsch | All rights reserved

Photo: Johanna C. Günther, Danielle Gluns, Julia Lisa Gramsch | All rights reservedWe distinguish these activities from those that primarily promote social inclusion. Activities aimed at social inclusion comprise the “involvement” in a civil society organisation, such as being an active member of a local sports club, access to societal systems such as the labour market or the education system and the possibility to build social relationships. Gaining access to societal systems can be a basis for more active participation: A person enrolled in school may learn about the functioning of the local system and opportunities to actively influence it, e.g., through engagement in local networks. Participation, in this sense, means that a person is able to actively shape a societal system, not only make use of it.

“The more contacts you have, the easier it gets to really participate.”

All of these activities – as stressed by the interviewee, a politically active immigrant – can contribute to a person’s sense of belonging and thereby strengthen a person’s motivation to participate in decision-making processes. For this initial motivation to turn into participation, a person must feel that their activities can trigger change. But immigrants feel this type of self-efficacy less than German nationals. Therefore, local authorities play a key role in encouraging immigrants to get involved, engage and participate.

“The more contacts you have, the easier it gets to really participate.”

Participation in rural areas

While much of the public discourse on the participation of immigrants focuses on urban areas, rural districts are also dynamic localities of participation. But sometimes participation in rural areas takes different shapes and occurs at different venues when compared to urban settings.

In the eleven rural districts we investigated through qualitative interviews, participatory processes were rarely institutionalised. Instead, local authorities focused on informal networks that bring together persons with and without a migration biography. Generally, we found an overwhelming majority of cases of “involvement” or “engagement” of immigrants but only few signs of fully developed instances of “political participation”.

Interviewees stressed the importance of civil society initiatives, such as Welcome Cafés or volunteers’ roundtables. While these activities are primarily aimed at fostering social contacts and relations, they also help to inform newcomers about opportunities to engage and partake in local decision-making processes. These low-threshold offers can provide the basis for more active participation. Interviewees also highlighted the essential function of networks, such as the Network Integration (district Börde) or the Network Asylum in Oberland (district Weilheim-Schongau), which aim to shape local migration policy-making. Importantly, these networks are collaboratively organised by civil society, welfare associations and local authorities, ensuring that the issues raised during network meetings come with the potential to make it onto the political agenda. We also came across thematic expert platforms, such as the Working Group of Integration Partners (district Bernkastel-Wittlich) and Integration Experts Roundtables (district Weilheim-Schongau) that meet in different constellations based on the issue at stake.

Even if these structures were designed to be inclusive, interviewees noted that immigrants are underrepresented in most of them. Reasons given were, for instance, a lack in access to some groups of immigrants, particularly immigrants from other member states of the European Union. Interviewees also complained that relevant contact persons were difficult to identify – on the part of local authorities as well as for various groups of immigrants. Lastly, immigrants seemed hesitant to engage in these networks due to language barriers.

These dynamics bear risks: Wherever individuals or organisations gather to discuss matters related to migration without including the voice of immigrants, paternalistic structures are reinforced. This makes it even more difficult for immigrants to participate in decision-making processes which may then fail to produce needs-based solutions.

What local authorities can do to foster participation of immigrants

Local authorities are powerful actors in building, adjusting and improving the structures that help immigrants to actively participate in local decision-making. In fact, our research shows that without public actors building and promoting participatory structures, institutionalised participation is less likely to occur.

This is why local authorities should encourage the formalisation of participation structures. In Germany, local authorities can establish migration councils as counselling bodies that must be consulted in all local matters relevant to immigrants. This way, migration councils have a defined role within the policy-making process. While an elected council is often difficult to establish in rural areas due to the small number of immigrants living there, a migration council can also be founded as a body of appointed experts with and without migration biographies. In addition, transforming networks founded by immigrants into formal associations should be actively supported by local authorities to increase their visibility and influence.

More than that, local authorities should encourage immigrants to participate not only in issues related to integration but in all public policy matters. Immigrants should not be reduced to their migration biographies but addressed as full members of the local community, with respect to their individual needs and interests touching on various local policy fields.

“Many immigrants don’t trust local authorities. Maybe they had bad experiences in their home countries. Authorities here could really make a positive change happen – if they actively cared.”

“Many immigrants don’t trust local authorities. Maybe they had bad experiences in their home countries. Authorities here could really make a positive change happen – if they actively cared.”

In our interviews with local authorities as well as civil society members, we were often confronted with the idea that immigrants, and particularly refugees, needed to be “taken by the hand” in order to be able to actively participate. This view portrays immigrants as a homogeneous group characterised by deficits that prevent participation. Such culturalising attributions and prejudices can severely impede participation and should be minimised. As the above statement by one of the interviewed civil society actors emphasises: Local authorities should live up to their role model function and launch a process of critical self-reflection to find out whether they enable or inhibit the political self-efficacy of immigrants. This process should include diversity trainings and more diversity-focused hiring policies to pave the way for comprehensive social inclusion and participation of immigrants in rural areas.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Eline Waerp

Eline Waerp