A higher unified system

Currently, South Tyrol mobility is recognized as a best practice at national and international level. The Val Venosta railway is a virtuous case, able to encourage the modal shift from road to rail. From 2005 (year of its reopening), the total number of users per year has reached two Million [2], with consequent problems in terms of capacity. Due to economic and environmental reasons, among others, the process toward electrification is going on with the aim to enlarge the service [2]. This approach may be extended to the entire South Tyrolean system. Compared to the Italian average, both the public transport (PT) supply and demand are higher than the national score (4.5 km of PT per 100 inhabitants, compared to 3.0; and 68.8 passengers per 100 inhabitants, compared to 47.7) [3]. These positive figures are possible thanks to the integrated approach of the Autonomous Province, which offers competitive connections, info-mobility system (Mobilità Alto Adige [4]), integrated ticketing services (Alto Adige Pass [5]) and harmonized timetables for the PT available in the region. All these features make the several available transport modes part of a higher unified system.

Three reasons that make cross-border transport challenging:

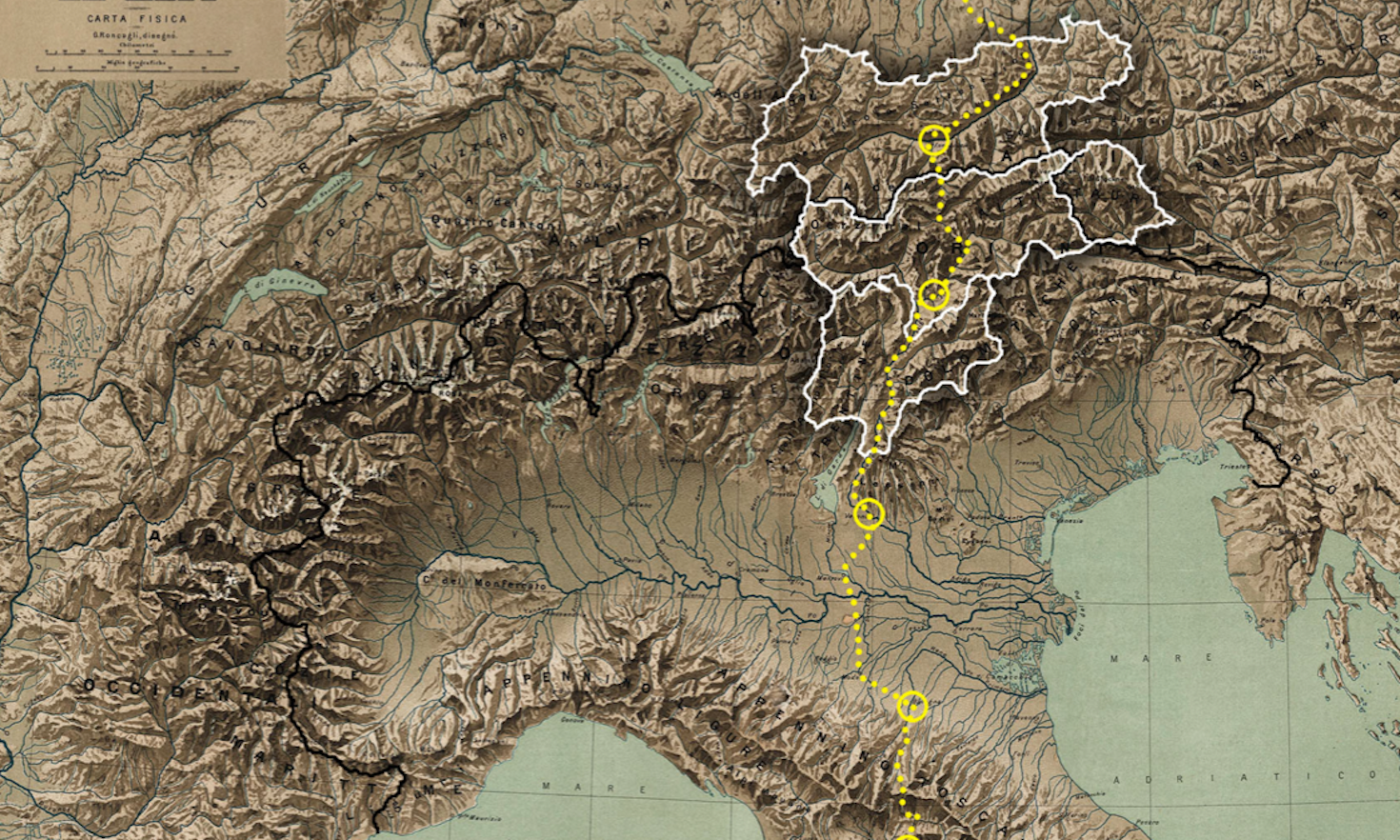

- Pay attention: scale matters. In this framework, each component of the PT system has its own specific role: trains are the backbone, with the aim to connect the main urban centers; urban busses provide connection within the main urban contexts; and finally, extra-urban busses, cable cars and funiculars increase the accessibility of remote areas. These three levels of service cooperate to cover three complementary scales: the inter-regional, provincial and urban ones. This approach is crucial, since it tries to keep up with the high “trans-scale” attitude of car, which typically allows users to leave any even remote location; and reach any city, industrial district, boarding region or foreign country, by their own way and always sitting. This kind of competition gets much more challenging at cross-border scale, where further political, technical and managerial difficulties arise. Indeed, currently, the cross-border PTs represent an open issue for South Tyrol.

- The challenge of long-distance and cross-border public transport. Looking at the demand side, the bigger is the commuting scale, the smaller is the share of PTs (and higher the share of private vehicles). Indeed, at urban scale, the share of people using car is 36%; at provincial scale, it almost doubles; and at cross-border, it is even higher (75%) [6]. This data is even more worrying considering tourists, since 90% of them reach South Tyrol by car, making it the second more attractive Italian region for leisure travel by car, and the third at European level (after the Italian Lake of Garda, and the German region of Algovia) [7]. This data is even more significant considering that tourism in South Tyrol is constantly growing as for both arrivals and presences [8]. Therefore, two opposite trends coexist in South Tyrol: a high tendency to slow mobility in urban centers. Trend confirmed by the high share of people commuting within the same municipality of residence (63.7%), and an even higher tendency to the use of private vehicles for large-scale commutes, and for the travel linking the main cities to their own surroundings. Trend confirmed by the high share of cross-border travels (third score among Italian regions) and of provincial travels (seventh score among Italian regions) [9].

- Who is the guilty? The weakness of South Tyrol PT at large scale and cross-border level may derive from several factors, regarding e.g. political features, transport supply, territorial settlements, demand trends, and cultural attitudes. Analyzing the PT supply, the cross-border services already offered are quite competitive. Both for Switzerland and Austria, regular cross-border buses or trains are guaranteed, harmonized timetables are provided, competitive commercial rail speeds are performed and only as regards ticketing and tariffs, some weaknesses exist. From a political perspective, collaborations among registered South Tyrolean and foreign transport operators are established (i.e. with the Swiss company AutoPostale, and with ÖBB as for Austrian trains); furthermore, the presence of the Euregio Tirolo-Alto Adige-Trentino [10] is a crucial resource for political synergies as well. On the other hand, the territorial settlement is a highly challenging feature to take into account. It influences the trend on demand and the cultural approach to mobility in general. Indeed, as all cities of South Tyrol encourage cycling and walking, just as the isolation of the peripheral areas discourages the use of articulated and not always effective multimodal chains. Consequently, the issues regarding the first and last miles influence users´ choices concerning an entire cross-border travel. This kind of challenge may be extended to the most of the travels addressed by citizens living in those isolated zones called “low-demand areas”.

To sum it up, the long-distance and cross-border travels highlight the need of a high development of a trans-scalar and comprehensive approach to PT. The challenge of providing competitive door-to-door solutions in rural contexts enforce this necessity since it represents a local problem with even large-scale reverberations. At the same time, the rural but international attitude of South Tyrol given by transnational cultures, landscapes and transport corridors, is a precious basis for the future development of a new way of imagining public transport. Innovative experiments in this sense are being developed, as the concept promoted by Mobility as a Service (MaaS) [11]. It considers mobility without classic distinction between public and private mobility. Behind this effort, there is also the challenge to find a balance between local identity conservation an international connection promotion.

Authors: Alberto Dianin & Cavallaro Federico

Useful links

- EURAC Research – Institute of Regional Development, Federico Cavallaro, 2017. Una valutazione dei costi esterni generati dal trasporto merci lungo il tratto provinciale altoatesino del corridoio del Brennero

- STA, 2018. Ferrovia della Val Venosta. Trenoaltoadige.bz.it

- RST – Ricerche e servizi per il territorio, 2012. Vincoli e potenzialità del sistema della mobilità nella provincia di Bolzano

- Mobilità Alto Adige. Sii.bz.it

- Mobilità Alto Adige. Tickets. Sii.bz.it

- Istituto provinciale di statistica ASTAT, 2017. Utilizzazione e grado di soddisfazione del trasporto pubblico

- ADAC, 2017. Classifica ADAC 2017: Wohin geht die Reise? Die beliebtesten Autoreisziele im Sommer 2017, Top Ten der Länder & Autoreisziele Sommer 2017, Die beliebtesten Regionen in Europa

- Istituto provinciale di statistica ASTAT, 2017. Andamento turistico – Stagione estiva 2017.

Ricarda Schmidt

Ricarda Schmidt