Übersetzen studieren im Zeitalter der maschinellen Übersetzung: Ist Deutsch eine Option?

Sandra Nauert

Sandra Nauert

Open Science hasn’t quite kept its promise to transform research into a fully transparent and accessible enterprise. One of its most bizarre excesses is the immense publication fees that scientists incur if they want to get published. Metascientist Sarahanne M. Field talks about how it came to this, where Open Science failed and how it could be improved.

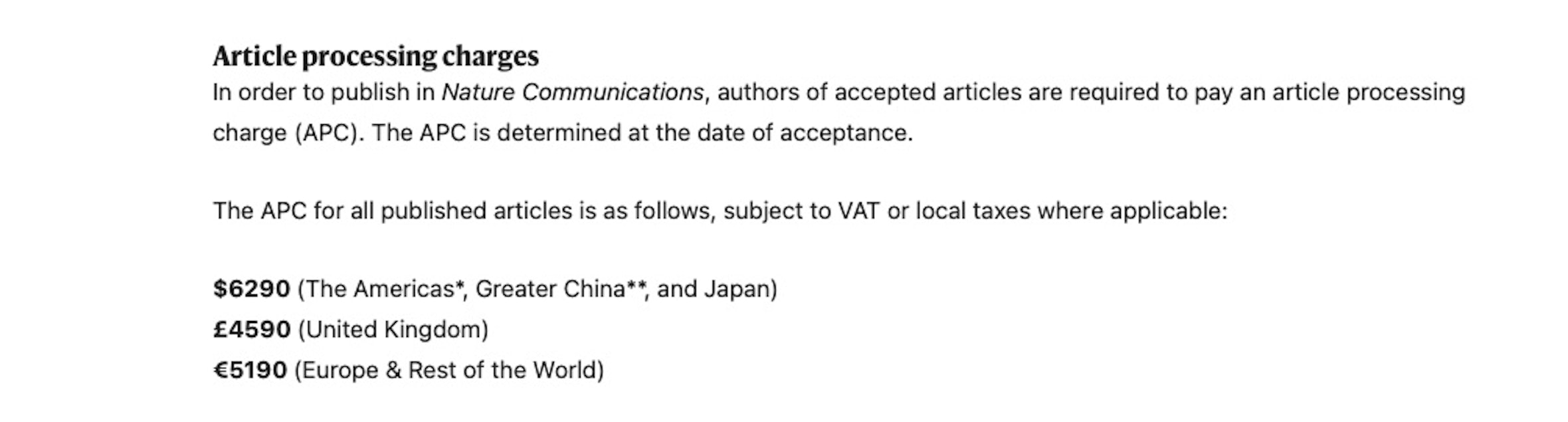

When you as an author pay for a journal to publish your work, that is what we call an APC. At this stage, your actual scientific work has already been paid for by an institution of a funding body. But now you need to disseminate your work, because in science, publication is a currency. So what you do is pay a journal to do that for you. The more prestigious the journal, the more you usually pay.

The fee covers the work for handling the article. This includes the typesetter and the copy editor. Some but not all journals use the fee to cover their editors’ salaries.

It does not tell you how much of your fee exactly goes to whom. Where it gets really bizarre is when they charge you higher APCs for colour print copies when in reality they don’t print one. At all. Most journals, with the exception of some big ones like Nature, Cell and The Lancet, publish straight into online repositories. But the journals still charge you extra for producing a print issue that doesn’t exist. And if you have a lot of graphs and tables to publish, they will increase that printing charge, too. It’s absurd.

No amount of proofreading and editing services justifies a $9,500 publication fee.

Sarahanne M. Field

With some glossy journals, you pay already thousands for getting it published as a closed-access article. That means nobody can read it for free. Not even you as the author. You would have to pay upward of 30 Euro per access to read your own intellectual property. The cost increases when you want to publish it as an open-access article that everyone can read. With Nature, in a domain like human behaviour, you will pay a couple of thousands for publishing it as a regular article. If you go open-access with Nature, that will set you back $9,500.

That’s right. The publishers are clearly all about generating profit. No amount of their proofreading and editing services justifies a $9,500 fee. A thousand, or one-and-a-half, I can understand that. But this is where they get greedy. You are selling your intellectual property rights for top dollar, and they’re not just charging you as the author, but they’re also turning a massive profit selling it.

More than that. It’s bullshit.

Not everybody does it, especially not the smaller, less-known journals. But the large and prestigious ones charge these outrageous fees because they can. As a scientist, you need them, or you don’t have a career. You need to keep publishing and get cited by your peers, and often. In order to get lots of these "good" citations, you need to publish in the big journals that get indexed by databases like Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar. The better your profile, the better you can climb the academic career ladder. This is according to the traditional model of science, anyway.

Yes, this is part of traditional science. As a scientist, you want to see your citations increasing each year, because it tends to mean you are relevant in your field. And you need more citations each year to climb the career ladder in academia. But that doesn’t happen if you publish with lower-quality journals or on pre-print servers that don’t require a fee for open-access publishing. You would get less visibility and hence less citations. And when you avoid APCs, you often don’t have peer review, which is possibly lowering the quality of your work. Again, this is the case for the pre-Open Science era.

Of course. Peer reviewers have enough expertise so that they can evaluate papers with a critical eye. They’ll look at a study’s methodology and tell you whether it is appropriate for the question you’re trying to find answers to. They’ll also tell you if you are measuring your data correctly and evaluate the entire paper using the underlying theory in the field. To do that, they must be experts in their domains. A noob cannot do it.

They get nothing. Whatever you pay in APC fees, nothing goes to the peer reviewers. You can imagine how happy they are about it. The journals tap into peer reviewers’ expertise, which they’ve often built over decades, including a decade or more of studying. Some are so unhappy, they started the 450 movement. They will only review their peers’ articles for a fee of $450. It would be easier if publishers just took that from those obscurely allocated APCs. But that doesn’t happen.

Status.

It should have been, yes. It should have been about breaking down barriers and rediscovering science’s core values. But here we are. If you want to publish an open-access article with a prestigious journal like Nature, you have to be one of the most wealthy people in the Open Science field. We are just further marginalizing the people who are already marginalized - all the while we are promoting those who already have an authority in academia. That is wrong. And I don’t know a single person in my field who doesn’t laugh at Nature’s so-called open-access strategy. To be clear, this is what the publishing industry is doing to open science: it is commercialising openness.

This is the Matthew Effect: the rich people in academia become richer, the already poor become poorer.

Sarahanne M. Field

Correct. We know that that is mostly white people in the global North. They are typically already quite advanced in their careers and often tenured. They also usually work in the more prestigious and wealthy research institutions, which in turn get better funding. These researchers have the financial means to pay these high APCs. It is basically the Matthew Effect: the rich people in academia become richer, the already poor become poorer. At the very least, I would say that it’s much harder to excel in science when you are from an underprivileged country.

I’m not remotely surprised. They have to choose between paying off their PhD or publishing an open-access article. In some countries in the Global South, the APCs exceed a scientist’s monthly or even a year’s salary.

It’s shocking. And it reflects what is wrong with the system.

There are different schools of thought on how to tackle it. A good friend of mine, Chris Hartgerink, left academia and founded Liberate Science, an organization that provides Open Science consulting, workshops and develops software to host open-access journals. Chris believes that it is difficult to stay in academia if you want to reform it. I have a different opinion. I think you can do a lot of good within the system, and I think leaving academia is not realistic for most people. So we are now working on a reform movement of the open science movement.

We need to work on two different levels. On the one hand, we are working on a grassroots level, which is how Open Science started in the first place. We are drumming up the will for change on a very low level, by meeting in independent scientist groups that don’t have any funding or recognition from policy and institutions yet. On the other hand, we also need to infiltrate higher levels of academia. Basically, we’re trying to get open-minded people into key positions like deans and rectors who then drive the reform movement.

That changes once you’ve gained critical mass. The more scientists demand that publishing becomes equal and affordable, the less the for-profit publishers can ignore them. Critical mass also enables us to get funding to do more research and outreach on reforming the Open Science movement. Which in turn prompts more scientists to join the movement and pave the way for even more investigations on how to do good science. We’re now starting to see how our movement spreads across conferences, and it has made it up to the highest academic levels.

The dean at the university where I received my PhD was also the chair of the committee for my doctoral defense. I had a chance to meet him beforehand and talk with him about my thesis, which was about the science reform movement. He was genuinely interested and excited about it. You see, the support for the cause is growing. And this leads to creating courses that will carry this knowledge on to the next generation of students.

At my former research group in Leiden, there is a whole branch of researchers that studies just that: how do we reward researchers right now, and how can we do it better? Again, much depends on the funders. The Dutch Research Council NWO is now requiring narrative CVs from candidates. They basically use candidates’ explanation of their experience and their quality as a researcher. They allow them to do it in their own words. So the candidates write up what they have achieved in story form. The candidates decide what they want to highlight from their career, rather than jotting down their h-index and journal impact factors. That is an example of a very tangible and not uncontroversial change to how we evaluate scientists. More and more funders like Wellcome are changing the way they are evaluating scientists’ performance. They are turning away from metrics and now look at qualitative aspects.

Some of them are really defensive. Them I call the Old Guard. They are defending an old system that is rotten at its core. Then there are also academics who are simply not aware of the problems, of the inequality. They are happily ignorant, and then people like me come along and tell them that academia is toxic. Of course that is disruptive and scary for them. But despite the pushback from the Old Guard, they won’t be able to resist change for much longer. There is pressure from every side in academia, not just from funders. Luckily there are not many such people. Most people I meet are genuinely excited for the challenge that reform brings to science.

The more chaotic side of me says, let’s get rid of today’s publishers since at their very core, they are completely toxic. They are one root cause of the problems in science because they have commercialized it. But the more rational side of me says that even these publishers play only their part within a context. They are part of a culture that has evolved. They didn’t just come out of nowhere. Publishers are the consequence of science being not only competitive but having a power imbalance.

It only works if we reduce publishers’ market power. We need to pull their business away from them, at least part of it. A lot of big European and US universities are already decreasing the attractiveness of the big publishers by cancelling their subscriptions with them. That is a huge slice of their revenues. But we also need to have viable alternatives. This is where it gets tricky. Chris Hartgerink who I mentioned earlier, created ResearchEquals, a modular publishing platform. It is based on the idea that you publish your research in chunks, not just as one static paper.

It’s the opposite of how open-access at the big publishers works. The more open you want to be, the less you pay. If you want to be restrictive and limit access to your journal articles, you have to pay more.

No. Not yet. There are currently no alternative publishing models that can hold water. But we are getting there, step by step. Projects like this are one of the cogwheels of this reform. Getting the right people in key positions takes time. You know the saying that science progresses one funeral at a time? That is perfectly true for publishing as well. The old way will eventually be replaced with better publishing models, fairer APCs and less inequality.

Dr. Sarahanne Field is a postdoctoral researcher at the centre for science and technology studies (CWTS) at Leiden University, the Netherlands. Her metascientific research focuses broadly on scientific reform: its community, culture, and practices. Her research suggests that despite its shared enterprise, scientific reform is a heterogenous, diverse body of sub-communities, who each contribute to the enterprise in their own unique way, and that progress in the reform movement is contingent upon recognising the diversity of its constituents. She is passionate about integrating reflexivity in quantitative disciplines, developing methods for selecting targets for replication, marrying open science with qualitative research and interrogating scientific reform practices and anticipating their downstream consequences. She loves distance running, with her favourite distance being the half-marathon.

*Correction: Springer Nature does offer partial APC waivers to researchers from some low income countries. Bolivia is in fact among these countries, while most other countries from The Americas are not.

Read more about the APC waivers: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/journal-policies/apc-waiver-countries

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Sandra Nauert

Sandra Nauert

Francesco Fernicola

Francesco Fernicola

Elena Chiocchetti

Elena Chiocchetti