A Quantum of Trust

Steven Umbrello

Steven Umbrello

The Coronavirus crisis which started at the end of 2019 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 have cut deep into the tissue of Europe’s socio-economic backbone, namely impacting its small and medium sized enterprises. On the basis of seven strategic axes, Roland Benedikter provides an outlook on the future perspective of European SMEs.

In March 2022, a third of the 3.8 million German SMEs which provide 60 percent of all German jobs, felt threatened by the consequences of the resulting supply chain problems, the rising prices of energy and resources, and strong inflation. In June this year, the Ambrosetti Club Economic Italian “uncertainty indicator” sunk to -21,1 percent, indicating a loss of confidence of entrepreneurs leading to stalling investments of SMEs in research and development and in innovation in general.

While the “bundled crises” of the recent years have darkened the outlook of one of Europe’s most important socio-economic branches, the calls for support for SMEs have multiplied – be it by targeted actions such as extra contributions and credits provided through single state spending programs allowed by the EU in a move to temporarily loosen the common debt rules; as well as by non-targeted support such as providing SMEs and their clients with bonuses for energy or lowering the VAT on certain products. So have the requests for new joint European future-anticipation and resilience programs following the model of the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, the EU Science Hub on Resilience and the EU 2020 Strategic Foresight Report, yet this time coming more “from the bottom up”, including crisis-anticipation programs tailored specifically by and for SMEs.

Despite all this, the European SME sector feels in flux in a way that has rarely been seen in past decades. As a result, one of the major questions regarding Europe’s future from an economic perspective, with far-reaching political, social and socio-cultural implications, concerns the outlook of its small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which also includes the skilled crafts and trades sector. The current re-globalization process is transforming the global order and globalization, in essence asking for “glocal” reforms of international arrangements. Re-globalization imposes not only threats and the need for soul-searching and self-examination as the prerequisites of forward-oriented change. It creates also new opportunities for innovation and – both territorial and trans-territorial – cooperation among differently structured SMEs. If SMEs evolve further in their strategic capacities and future preparedness, this could become an important factor of “capillary” economic and social resilience in upcoming post-Covid-19 and post-Ukraine war times not only for Europe, but also as part of the international political economy and as one crucial trajectory of global policy.

According to pan-European data of the European Parliament and European SME associations, “22,5 million SMEs in Europe employ almost 82,4 million people. SMEs in Europe count for 99,8 percent of all enterprises, 2/3 of employment and close to 53 percent of the added value created in the European Union. These enterprises play a decisive role in Europe’s economy and society, are drivers of innovation and ensure social and regional stability.“ The skilled crafts and trade sector is generally regarded as a sub-sector of SMEs, but with some specific characteristics and peculiarities.

As it has long been known, SMEs and crafts are structured differently from region to region across the north, south, east, and west of Europe, and therefore require differentiated continuity and innovation strategies. One effect of differing organizational patterns and legal and economics contexts is that SMEs are poorly related to each other and have not been evolving jointly. SMEs suffer from poor interconnections between the North-South and East-West axes. They are often lacking both trans-regional and trans-sectorial exchanges among their peers, as most SMEs are based in regional rather than national or transnational settings. International organizations which represent the crafts sector, such as INSME, the International Network for SMEs, or SMEUnited remain rather marginalized in terms of international “politics that count” and are often still not considered as macro-factors in their own right. Nevertheless, their importance for local communities is indispensable, as, for example, the research of the OECD “Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities” indicates. What many SMEs have in common is that they represent the basic framework of circular economic cycles both in highly- and less-developed European societies. They constitute a constantly self-renewing format of entrepreneurship that relies on familiar and cooperative environments, which contribute to making them effective due to their advanced level of short and often independent supply routes.

Indeed, in contrast to large multinational corporations or the transnational industries which are well represented in politics and European bodies, SMEs are predominantly regionally and locally anchored despite some partial supra-regional competition. For this reason, they serve as “glocal” stability factors, anchored in the local economy rather than in the globalized world, although being dependent on both. As such they deserve both special attention and coordinated international protection for their foreseeable role in limiting the time-delayed economic fallout at the end of the Covid-19 crisis phase and in a Post-Ukraine Europe ahead.

SMEs and crafts have held up local economies like a safety net. Due to their close-range everyday services, which are often tied to communities of labor-sharing and resource-exchanging peers, the basic framework of normality could continue to exist even when a multipolar crisis hit and disrupted globalized networks.

Roland Benedikter

On the European Union stage, a common factor of SMEs is that they face various levels and types of systemic challenges. First of all, over the coming years they will be particularly affected by technological innovation, which will require some serious re-adjustment. While some SMEs have already perished during 2019-22 ‘s Coronavirus crisis due to lack of technological readiness and adaptability, many have survived but still struggle with the leap into fully-fledged digitization.

At the same time, certain SMEs have clearly proven to be the epitome of multi-resilience during “bundled” crises. Europe has been witnessing this with particular clarity during the Coronavirus crisis and is seeing this again to a certain extent with regard to the economic fallout of the Russia-Ukraine war since February 2022. In Covid-times, according to international lenders particularly the German “Mittelstand” despite partly entering a state of psychological depression provided an example of how to deal with a contemporary systemic crisis: “Keep spending on research and development even if sales drop, build a financial buffer so you can craft a long-term business plan, be flexible with dealers to keep supply chains intact, have an innovative mindset and see crises as opportunities.“

Despite all odds, something similar has been happening since the start of Russia’s 2022 Ukraine war on 24 February. SMEs and crafts have held up local economies like a safety net. Due to their close-range everyday services, which are often tied to communities of labor-sharing and resource-exchanging peers, the basic framework of normality could continue to exist even when a multipolar crisis hit and disrupted globalized networks. This cornerstone of the continuity of Europe’s economies also influences contemporary ways of life across different European regions, nations and cultures. Its future depends, in essence, on seven main development axes.

These axes are, to put it in the shortest possible way:

1. Strengthening the interconnectedness of SME strategies with encompassing European and other grand global development strategies.

In recent years, many European regions have invested a great deal in thinking ahead to the future. Future-oriented development strategies of inter- and trans-disciplinary character have emerged across a variety of issues: on sustainable spatial productivity, smart and green energy and decentralized social technologies. Although poorly interconnected, many of these strategies pursue ultimately converging goals. To mention just one example, the “RIS3 strategy” is a region-centered strategy cluster that was introduced in December 2013 by the European Union as a prerequisite for EU funding. RIS3 is the acronym for “Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization,” which in theory all of the more than 1100 EU regions (according to NUTS3 classification) and/or 242 EU regions (according to NUTS2 classification) must present when applying for EU financing. The RIS3 is intended to help develop the EU according to regional and local areas of strength. Other global players such as China and India are also in the process of following this “structured differentiated development” example. Proposals for the RIS3 strategy usually include “euregional” and “glocal” solutions for sectors such as, to mention just a few examples, Automation, Smart Processing, Agri-Food Nutrition, Medical Research, Quality of Life, Smart Energy Systems, Energy Efficient and Sustainable Construction, Circular Economy, Smart Centers and Smart Peripheries. Creating ways to interconnect the respective approaches across regions by better embedding specific SME and craft strategies will be crucial in strengthening the role of EU-sub-bodies in their surrounding ecosystems.

2. Improving life-long learning options.

For all SME and crafts sectors, which are generally strongly linked to territorial contextualization, education and training must be key concerns for a sustainable future. The half-life of know-how based products is shrinking and technological innovation accelerating. As a consequence, change is speeding up. Specific education for incoming or potential futures, however, does not appear in many regional or local development strategies as a separate topic or project, since – like the creative industries – it seems to be implicit in and has an impact on, all sectors. This lack should be questioned, since innovations in the field of education become as important for the future of SMEs and crafts as technological innovation, because the latter cannot function without the former. This is particularly valid for life-long learning and the need for constant know-how upgrading, but also regarding the challenge of improving social capacities of networking, cooperating and interacting. To make the transition toward emerging forms of knowledge reasonable and to keep the SMEs “embedded” in the overall drive of societies, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN Agenda 2030 could be used even more explicitly as an orientation framework for “educational adaptability”. This should include the UNESCO strategic framework 2022-29 in particular.

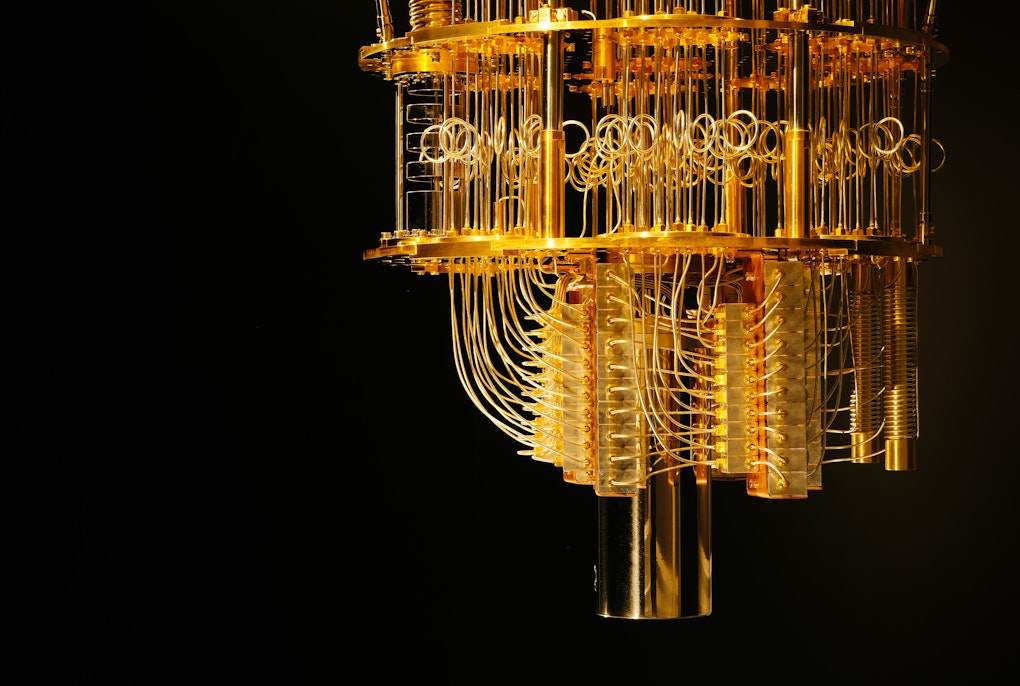

3. Incorporating new, avantgarde- and experimental technologies.

The above mentioned regionalization of the EU’s funding scheme with strong regard to scientific innovation also points the way to a broader technologization of SMEs. For example, in the coming years SMEs and the skilled trades will become gradually more involved in the new field of “New Human Technologies”, including Human-Machine-Convergence, because people are using increasingly intelligent machines which are in the process of “converging” with humans. As noted by the European Investment Bank and European Commission’s EU Report of 2021 “Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain and the Future of Europe: How Disruptive Technologies are Generating Opportunities for a Green and Digital Economy”, “Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain technologies have the potential to revolutionize the way we work, travel, relax, and organize our society and daily lives. Already, they are improving our world: Artificial Intelligence has been critical to accelerating the development and production of Covid-19 vaccines, while Blockchain has the potential [...] to also help us better track and report greenhouse gas emissions, streamline commercial transportation, and create true privacy. The advancement of both technologies – guided by ethical and sustainable principles – has the potential to create new pathways for our growth and drive technological solutions that make our societies truly digital, greener, and ultimately keep the planet habitable.”

However, the same report also indicated that, representative of the need for a general change of mind, “Europe needs to close an investment gap of up to €10 billion that is holding back the development and deployment of AI and Blockchain technologies”.

This is also valid, in capillary ways, in the field of SMEs and the skilled crafts sector. As the same study pointed out, “the highest number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) involved in Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain can be found in the United States (2,995), followed by China (1,418) and the EU27 (1,232). The United Kingdom is another notable player (495). Within the EU27, the highest number of companies is located in Germany and Austria, followed by southern Europe, France and central, eastern and south-eastern Europe (EU13).“

At the same time, the report underscored that “the EU27 has more specialised researchers than its peers, and typically produces the most technology-related academic research. Europe also has the largest talent pool of researchers in Artificial Intelligence, with an estimated 43,064 in the field (of whom 7,998 are in the United Kingdom), compared with 28,536 in the United States and 18,232 in China.“ Which is good news in view of the generally more competitive environment ahead – also in the field of SMEs which nevertheless urgently need a broad and in-depth offensive in Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain upgradings.

Without doubt, the integration of Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain, SMEs and crafts offers a multitude of still untapped opportunities. For example, Enea, the Italian National Research Institute for New Technologies in the Energy Sector, pointed out in June 2021 that they had created a platform capable of self-noting in real time the consumption of energy communities (including SMEs) via decentralized blockchain technology. Derived from this, Enea announced that it can take actions towards users, including firms, to automatically reward them when they try to reduce their consumption in certain timeframes. The users themselves can understand the imbalances of the network in real time and change their consumption habits. According to Enea, decentralized Blockchain certification is also possible for the injection of energy from renewable sources into the grid, thus increasing the autonomy and energy self-management of SMEs noticeably.

Summing up, new technologies, if efficiently implemented, can bring immediate benefits to SMEs and crafts especially regarding energy and resource consumption, logistics and real-time overall control, autonomy from centralized bureaucracies and individually tailored project management. EU regions, however, still present a North-South gap. They should take their current cues from Germany rather than Italy when it comes to investing in their own future, if one looks at the bare figures. For example, Germany invested €1,963 billion in AI and Blockchain technologies in 2010-19, France €1,269, which together accounted for 70 percent of the EU total. The remaining 30 percent in that timeframe were distributed among the other EU countries, with Belgium (€238 million), Sweden (€195 million), and Ireland (€182 million) standing out, while Austria (€87 million) and Italy (€38 million) ranked near the bottom. This should change and pave the way for greater balance, also for the sake of SMEs’ modernization which is overdue.

4. Developing multi-resilience for bundled crises.

Although they are themselves key players in the field of global resilience, a key issue for SMEs and the skilled trades remains sustainable and multiple-disciplines-based crisis resilience. As the Coronavirus pandemic has shown with brutal clarity, the re-globalizing world no longer lives in the age of sectorial crises, but of “crisis bundles” or “bundled crises”. Bundled crises come as multi-sectoral, systemic, and inter- and transdisciplinary. They act at the interface of the local, the national and the transnational, affecting all involved levels and players in one way or another. It is therefore advisable to include SMEs and the skilled trades in the elaboration of more in-depth, deliberately multi-sectorial strategies. On a European level, systemically interrelated work on this is currently just beginning. Among the new approaches is “multi-resilience”, which brings together various concepts of resilience that often diverge according to sectors and specializations and are sometimes poorly integrated into individual SME work realities. Here, SMEs and the skilled trades, aiming at creating the basic structure of a less top-down and more “horizontal” global resilience network, can play a pragmatic and use-oriented integrating role between different resiliency approaches. Social scientists such as Charlie Edwards or Karim Fathi speak of four dimensions in which the “multi-resilience” approach can bring immediate gains to SMEs and the skilled trades: 1. robustness, 2. redundancy (i.e. variability in the fulfillment of basic tasks), 3. resourcefulness, 4. speed.

5. Activating hitherto (under)utilized human resources.

The shortage of skilled workers remains a problem for SMEs throughout Europe, both in higher and less developed countries. At the same time, developed countries in particular hold the potential of the large and still largely untapped reservoir of migrants and refugees. According to statistics, of the widely unprecedented refugee and migration flux that has occurred since the 2014-15 European migration crisis, despite all public efforts only a limited portion – in Germany, for example, until May 2020 roughly 29 percent – have found permanent work. Although the situation varies according to different nations, with somewhat better statistics, for example, for the Ukrainians that fled the Russian invasion to Poland where more than 100,000 have found work within a short timeframe mainly in the industry and the SME sectors, the overall development pattern remains slow and insecure. This weakens the European welfare state and makes integration more difficult. The skilled trades sector can make better use of this resource of potential workers in terms of regional innovation and circular economy, and at the same time function as integrator. Language, enrollment, and qualification measures are just as useful in promoting integration as cultural inclusion and gradual empowerment to citizen autonomy. SMEs could promote integration into local SME work practices with bonus point schemes, supported by adaptations of regional and sectorial integration laws. Positive policy proposals from the skilled trades, including specific needs assessments, should be incorporated into existing European migration programs at the national level and also for provinces, districts and municipalities. The skilled trades can take a more active role in the area of human potentials based on their practical needs and thus, directly and indirectly, help policy makers in their decisions for the greater benefit of society.

6. Implementing structured anticipation methods precisely tailored to SMEs at various levels and for different sectors, for example in the form of UNESCO Futures literacy (FL) and Futures literacy labs (FLL).

How can SMEs become more future-oriented by developing a basic future-prepared mindset? How can they use the future as a capacity, i.e. a practical human capability, in – and for – the present?

“Real-World laboratories” are a proven format of engaging futures planning and have been there since the 1990s. In addition, since the 2000s there is the innovative UNESCO format of “futures education,” or “Futures literacy”. This is a method to anticipate multi-dimensional developments tailored specifically to the 21st century. Futures literacy has been expanding globally over the past few years. It works with “Futures literacy laboratories”. UNESCO Futures literacy laboratories are the latest step in the “Living Labs” or “Real-World Laboratories” idea, as defined, for example, by the European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL). They use a refined methodology for all levels of education, including generations, professions and populations, providing an inclusive learning tool that enables the future to be addressed by everyone in their everyday lives. Futures Literacy is not just about planning (forecast) or looking ahead to possible future scenarios (foresight), as has mostly been the case in the past, but is also about working with futures in the present, or with co-creating the present out of anticipation. The development of this capability is likely to become one of the most important ones in the coming years. It still lies largely fallow in the SME sector, yet holds the potential for motivation in immediate interaction, especially on a human level. For a sustainable SME sector that not only future-proofs its machines, but also its people, this capability will be essential in the upcoming re-globalized world. It also enables connection to global trends and more intense exchange of SMEs with international organizations such as UNESCO or OECD.

7. Developing “Glocalization” to become a formative task.

In order to place multi-resilience and future-education into the web of existing European country, district, and community strategies involving SMEs, more education on the bigger picture of the nexus global-local and its role in local economic circles is needed. Continuing education on the changing European and international environment as related to “glocalization” makes sense if it inspires the mobilization of ideas “from below”, if it is presented in practice-oriented ways, and if it is developed jointly by SMEs, crafts organizations, a variety of economic and political actors, civil society representatives and social scientists. As mentioned today in the social sciences we speak of the age of re-globalization: of a disruptive phase in the formerly familiar patterns of globalization. Glocalization, i.e. the balancing and mutual adaptation of the global and the local, is one answer to the new challenges arising with recurring bundled crises. Whether it wants it or not, the SMEs and skilled crafts sector is called upon to play its role in this process because, especially in countries with an orientation toward small and medium-sized enterprises, some of the burdens of the respective reforms and recalibrations will fall upon it. For this reason, SMEs, and the skilled trades – not just the economic elites – should prepare themselves from early to the upcoming change on across the board. Glocalization training will enable them to play a credible role in the development of upcoming macro-, meso- and micro-economic reform discourses.

With these seven strategic axes implemented in interrelated, practical and pragmatic ways, lessons could be learned with regard not only to the bundled crises of the recent years, but also concerning future “capillary” European cooperation and integration, and the paths forward to undertake from here. If the necessary post-Pandemic financing is found to push SMEs towards further future-orientation, multi-resilience and smart digitization offensives – for example in the framework of respective OECD proposals and the “Digital Europe Programme” –, the seven axes are open for practical, perhaps even interactive realization. What Europe’s SMEs need now in the first place is a trans-national exchange of “best practice” examples – especially those that pursue similar training and education paths. Education, technology and science patterns are now in the process of being mutually adapted by European regions as well as by nation states in their development strategies. Among the respective drivers are not only the EU, but increasingly also its neighbors and allies. This makes the exchange and mutual assistance in the implementation of the seven strategic axes even more relevant – and more promising – in the now needed perspective of European multi-cooperativeness.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.