magazine_ Article

“I could never be sure that I would be understood”

Communication difficulties in extreme rescue operations

The successful rescue of seriously injured people in extreme situations is dependent on successful communication, both within the rescue team itself and to people that they encounter. So, how can you develop these vital skills? Emergency physicians from all over the world came together at terraXcube, our extreme climate simulator to find out.

The entrance area of terraXcube – Eurac Research’s Center for Extreme Climate Simulation is getting crowded. Experts and 40 emergency physicians from all over the world, who have accepted Eurac Research’s invitation to spend two days training in the use of innovative technologies and procedures under difficult conditions in the mountains - in wind, cold and darkness - are packed around the exhibition tables. Giacomo Strapazzon, Head of the Institute for Alpine Emergency Medicine, concludes his welcome address to them with the sentence: “Let’s learn and be safe in adverse conditions.”

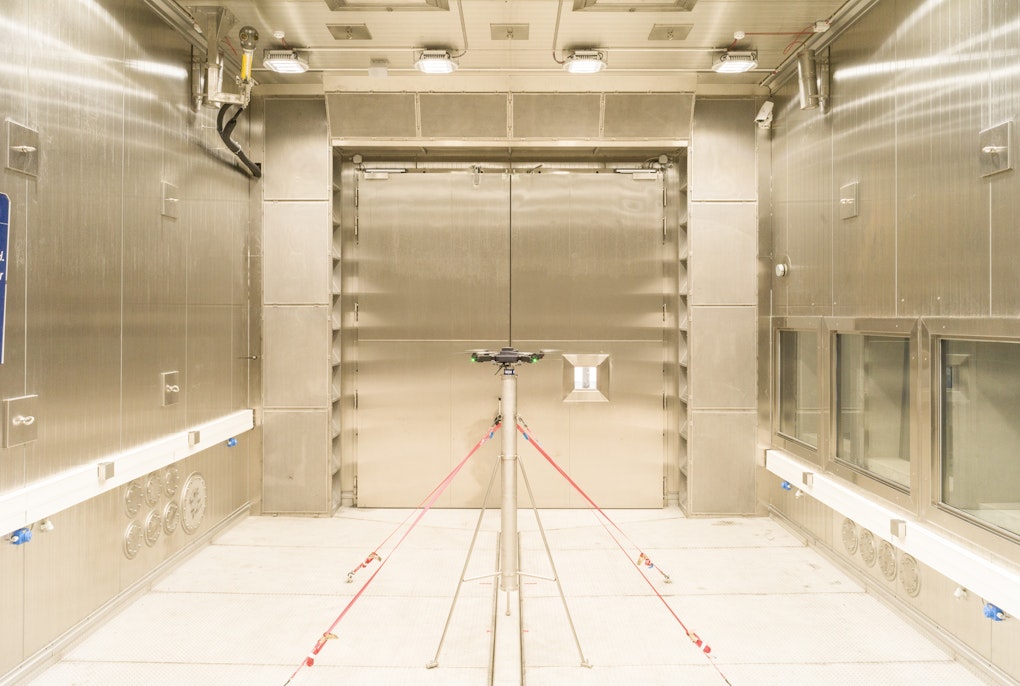

The extraordinary training follows a simulated rescue scenario in the Large Cube, the largest chamber of the extreme climate simulator. Inside, the participants encounter environmental conditions similar to those in the high mountains. The groups, formed in advance, consist the following rescues teams; three female emergency doctors, two male emergency doctors and two mountain rescuers who take care of technical matters. After a short briefing in which the instructions to “act as realistically as possible and be quick as you can, and take as long as you need,” the team is equipped for the high mountain emergency mission. Two of the test doctors who have traveled from afar are given protective clothing, the others have their own: the logos and lettering of the Austrian Mountain Rescue Service, the Bavarian Mountain Rescue Service and the American Mountain Rescue Association can be seen on the jackets and helmets. While the rescue team familiarizes itself with the equipment provided by Aiut Alpin Dolomites, climbing harnesses are put on and headlamps are attached, final preparations are also underway in the technical control room.

The interior of the Large Cube can be seen on several monitors. From here, Carsten Patzelt, Senior Technician of the terraXcube, controls the climate conditions in the chamber. Lights are still illuminating the set-up scene, in but soon the participants will find themselves in the dark. A huge boulder block mimics a mountain peak, around which the “wind” from two turbines is already whistling. “The instructors tell me when they need wind and how much,” explains Patzelt as he pushes a regulator upwards.

“Can you switch off the lights, please?” sounds through the intercom, Patzelt flicks a switch and it the screens go dark. White dust particles shoot past in the fierce wind on the black and white image on the monitors. In the meantime, the roles in the emergency team have been assigned. The team leader uses a walkie-talkie to communicate with the trainers from Eurac Research. “The rescue center” has now been simulated.

It all starts with an emergency call

And then it begins: the emergency call center reports a mountain accident. After a brief phone call, the team leader shares the scant information with the rescue team: a group is in distress in the mountains, it’s cold, bad weather is approaching and darkness is on its way. The group has been located, but contact has been lost and there is no further information. The rescue team reaches the casualties an hour after the emergency call has been received.

That’s the cue. The trainers open the thermal door to the Large Cube and the rescue team enters the scene. An icy cold wind hits them. The door is pushed shut and it is dark. Only the headlamps on the helmets light up the room here and there. A light board on the wall shows the temperature: -17,5 °C. The screams of an injured person drown out the wind turbines, and the team tries to get an overview of the situation.

It slowly becomes clear that there are three injured people: casualty number 1 - played by a volunteer, is lying in a narrow space between the wall and the climbing cube. He appears to be conscious but seriously injured. His right leg is twisted into an unnatural position and an ice pick is stuck in his left shoulder. An emergency doctor kneels next to him and tries to talk to him. The injured man’s thin voice is barely audible in the howling wind.

Loud cries for help come from behind the rock. A mountain rescuer and a medic clip in with their carabiners and begin to ascend the boulder. Once on the other side, they abseil down into a narrow hole in the rock. Down here, somewhat protected from the icy wind, casualty 2, also a volunteer, sits leaning against the rock face, holding his obviously broken wrist and screaming in pain. Just above him hangs casualty 3 in a climbing harness. The lifelike dummy simulates someone who has fainted.

First, casualty 3 is slowly lowered down, the doctor checks his vital signs and begins resuscitation. He calls for reinforcements, but the wind is so loud that his colleagues can’t hear him. The emergency doctor will later say about casualty 2: “He was crying, so I knew he was okay.”

Back to casualty 1: His leg has now been stabilized and although he is wrapped in a rescue blanket, he is shaking all over. The two doctors, working with their bare hands don't seem to notice the freezing cold. In order to communicate, they have to shout against the wind. The darkness, which is only broken by the beams of their headlamps, makes communication even more difficult. One does not always seem to understand what the other is trying to say.

In the meantime, the emergency doctor behind the rock has managed to make contact with the team leader, and now there are two injured people, two doctors and a mountain rescuer in a very confined space in the hole in the rock. While casualty 2 is still moaning, the dummy is being tirelessly resuscitated. Here too, the conditions make communication between the doctors and the rest of the team on the other side of the cliff visibly more difficult. Finally, everything is ready to pull casualty 2 out of the narrow space and lower him back down on the other side. He is escorted to a sheltered place and the team leader stays with him from now on. After gaining an overview of the situation, she calls the emergency center and orders the rescue helicopter. Shouts can be heard through the wind from the darkness: “Where is the blanket? The casualty is shivering badly.”

In the meantime, the two emergency doctors in the rock hole have managed to resuscitate casualty 3 and bring him out from behind the large rock. Casualty 1 has also been prepared for transportation. The thermal door opens, the two seriously injured individuals are carried out, casualty 2 can leave the room independently and get into the imaginary rescue helicopter.

Debriefing

Warm air starts to recirculate, and with it the lightness returns. The climatic conditions in the Large Cube made the situation seem very real and almost made the rescue teams forget that it wasn’t a real emergency. Now the tension is gradually disappearing from their faces and they are laughing and joking again. “I died for science,” a voive pipes up from one of the thickly wrapped emergency stretchers. It is casualty 1, who has not yet been released from his hypothermia rescue bag.

After everyone has got rid of their climbing harnesses, helmets and functional clothing, the group meets with scientists from the Institute for Alpine Emergency Medicine for a debriefing. This debriefing in the warmth is just as important for the training as the simulation of the mountain accident itself. It is not only about evaluating whether and how the team has mastered the task, but also about sharing and discussing the knowledge and experience gained. In this way, the experience can be analyzed and used as preparation for future assignments. This helps to process things on a personal level and helps the team to improve.

It soon became clear that the extreme climatic situation complicated communication at all levels: between the doctors, with the mountain rescuers and the team leader, as well as with the rescue center at the hospital. Unsurprisingly, experienced teams had it a little easier, but overall, everyone agreed that the biggest difficulty was passing on all the relevant information quickly and safely to their team as well as to the outside world. “Every word I wanted to say, I had to scream it out, and I could never be sure if it was understood.”

Simon Rauch, emergency physician and researcher at Eurac Research, also confirms that operations in the mountains present rescue teams with completely different challenges to emergency medicine in the city. This is why it is so important to test how life-saving interventions can be carried out on seriously injured people, even in difficult terrain and under extreme conditions.

It became clear that being prepared for rescue operations in extreme situations requires more than just knowledge and practice with the latest technologies. Soft skills such as teamwork, communication skills, leadership and situational awareness also need to be trained so that communication works even under adverse conditions.

ICAR-Training in terraXcube

The exercises were held in October 2023. The medics invited were members of the International Commission for Alpine Emergency Medicine ICAR, whose annual meeting was held in Dobbiaco this year. In addition to the mountain rescue accident under extreme conditions, they tested a range of innovative emergency medical procedures. In addition to the smallest ECMO machine in the world (Colibrì, Eurosets s.r.l., Medolla, Italy). The retrograde balloon occlusion of the aorta, or REBOA for short, was also tested. This procedure is normally used for severe internal bleeding. A small balloon is inserted into the aorta and inflated there to stop the bleeding. Experts from the Ospedale Maggiore in Bologna already use this technique in their rescue helicopter missions and passed on their experience during the training in Bolzano. Difficult intubation techniques were also practiced, once at normal temperatures and, for comparison, also at minus 20 degrees Celsius.

As more and more people are venturing into the mountains and into the high mountains, and climate change is making natural events such as landslides and rockfalls more likely, extreme rescue situations will become increasingly common. “We assume that accidents and emergency situations in difficult conditions will increase in the future. This training in the terraXcube is a valuable opportunity to prepare rescue teams for this - also with a view to expanding the training of the new generation of specialist colleagues,” emphasize Hermann Brugger and Luigi Festi, co-director and coordinator of the international Master’s degree course in Alpine Emergency Medicine, which is organized by the University of Insubria, the University of Milan-Bicocca and Eurac Research.

Partners of the two-day training course at terraXcube were the ICAR (International Commission for Alpine Emergency Medicine), the University of Bicocca in Milan, the University of Insubria, CNSAS (Corpo Nazionale Soccorso Alpino e Speleologico), the South Tyrol Mountain Rescue Service, the South Tyrol Ambulance Service and Aiut Alpin Dolomites.