magazine_ Article

Where research and industry meet

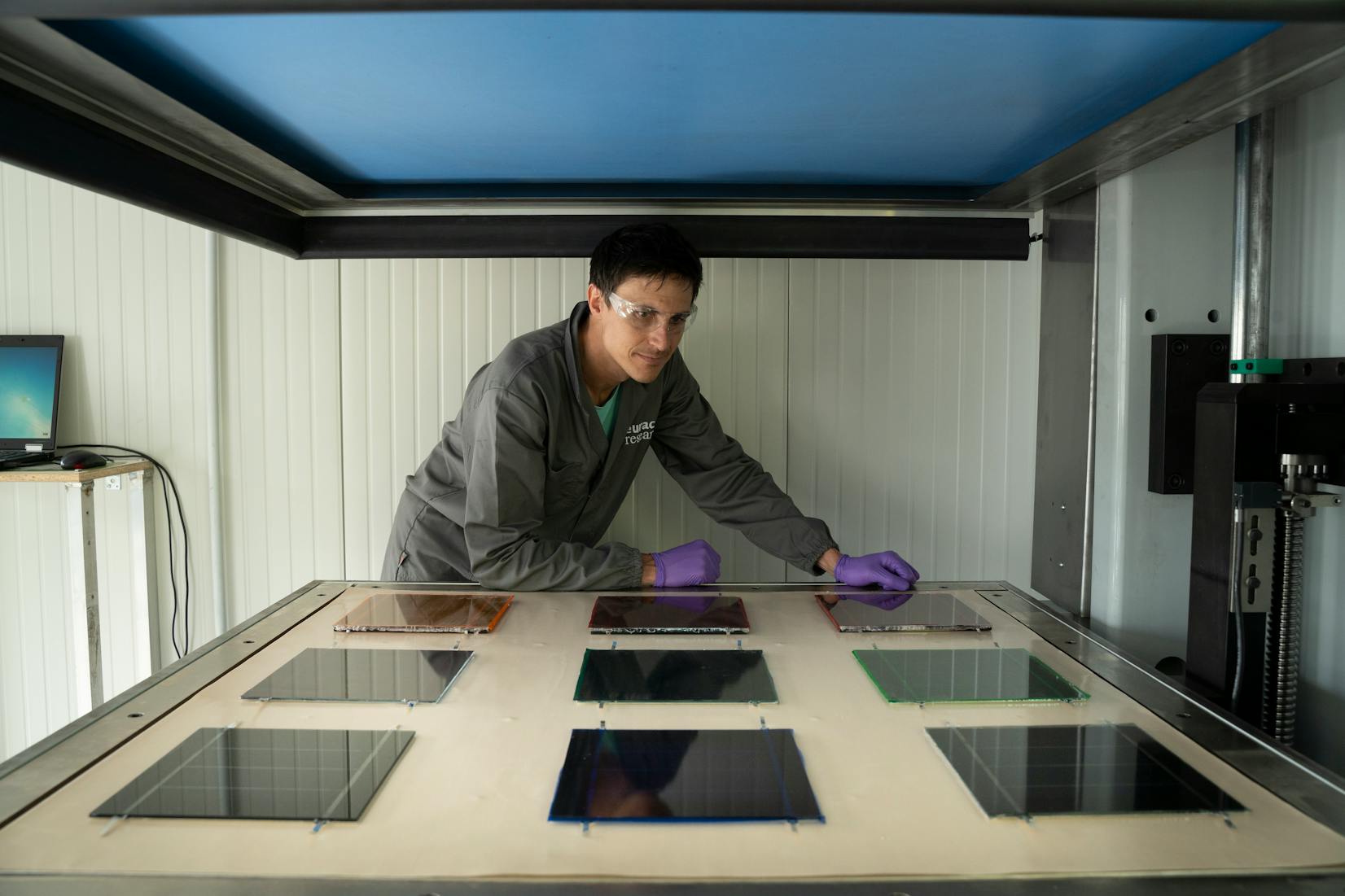

Eurac Research inaugurates a new laboratory for photovoltaic module prototyping

From design to module assembly, from laboratory to field testing, the photovoltaic prototyping lab at our Institute for Renewable Energy is a hub where universities and industry can contribute to the realization of new technologies.

It starts with a rectangular sheet of glass, just a few millimeters thick, and leads to a device that can convert solar radiation into electrical energy. As of today, the process that enables such a seemingly simple object to become such a sophisticated one is taking place at Eurac Research’s Institute for Renewable Energy.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

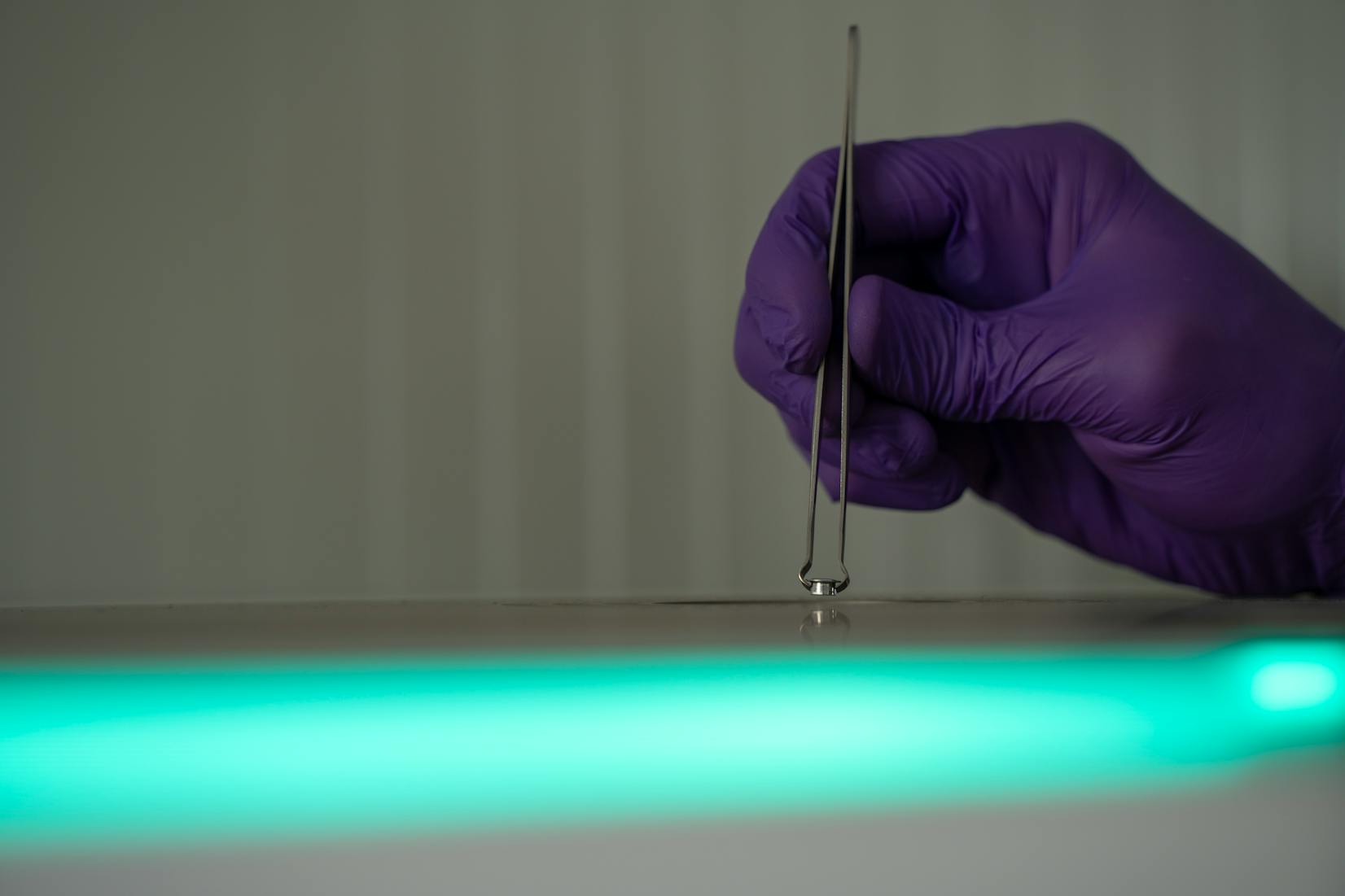

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni“We can think of assembling a photovoltaic module a bit like preparing a cooking recipe,” says Jordi Veirman, senior researcher in the R&D field. “We have a list of ingredients, each of which must be added in a predetermined order to fulfil a specific function, and the recipe can vary according to the final use intended for the module”. In general, a module consists of a first layer of glass on top of which a layer of encapsulant – a material that provides adhesion between the solar cells – is added.. Then the solar cells are laid down, after being connected to each other with copper ribbons in a way to provide the desired electrical power. This is followed by another layer of encapsulant and, finally, a support layer. Once all the ingredients of the “recipe” are combined, they are placed into the oven. In the new laboratory it is a laminator: a device that presses and heats the component parts to join them together, resulting in the production of the modules.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De GiovanniFor any recipe to be a success, the “baking” of the module components must take place at the right temperature and duration. “To obtain strong photovoltaic modules, the chains of molecules that make up the encapsulant must form a sufficient number of bonds with each other,” explains Jordi Veirman. The temperature and duration at which these bonds form best, without altering the mechanical properties of the encapsulant, is determined using another instrument: the differential scanning calorimeter. Through this instrument, then, the ideal processing conditions can be traced back to high quality modules.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De GiovanniWhile the differential scanning calorimeter measures the thermal properties of materials, the spectrophotometer measures their optical properties. “With the spectrophotometer, we can determine, for example, how much light passes through the glass front cover of the module and then reaches the photovoltaic cells,” says Gabriella Gonnella, an engineer specialized in renewable energy production.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

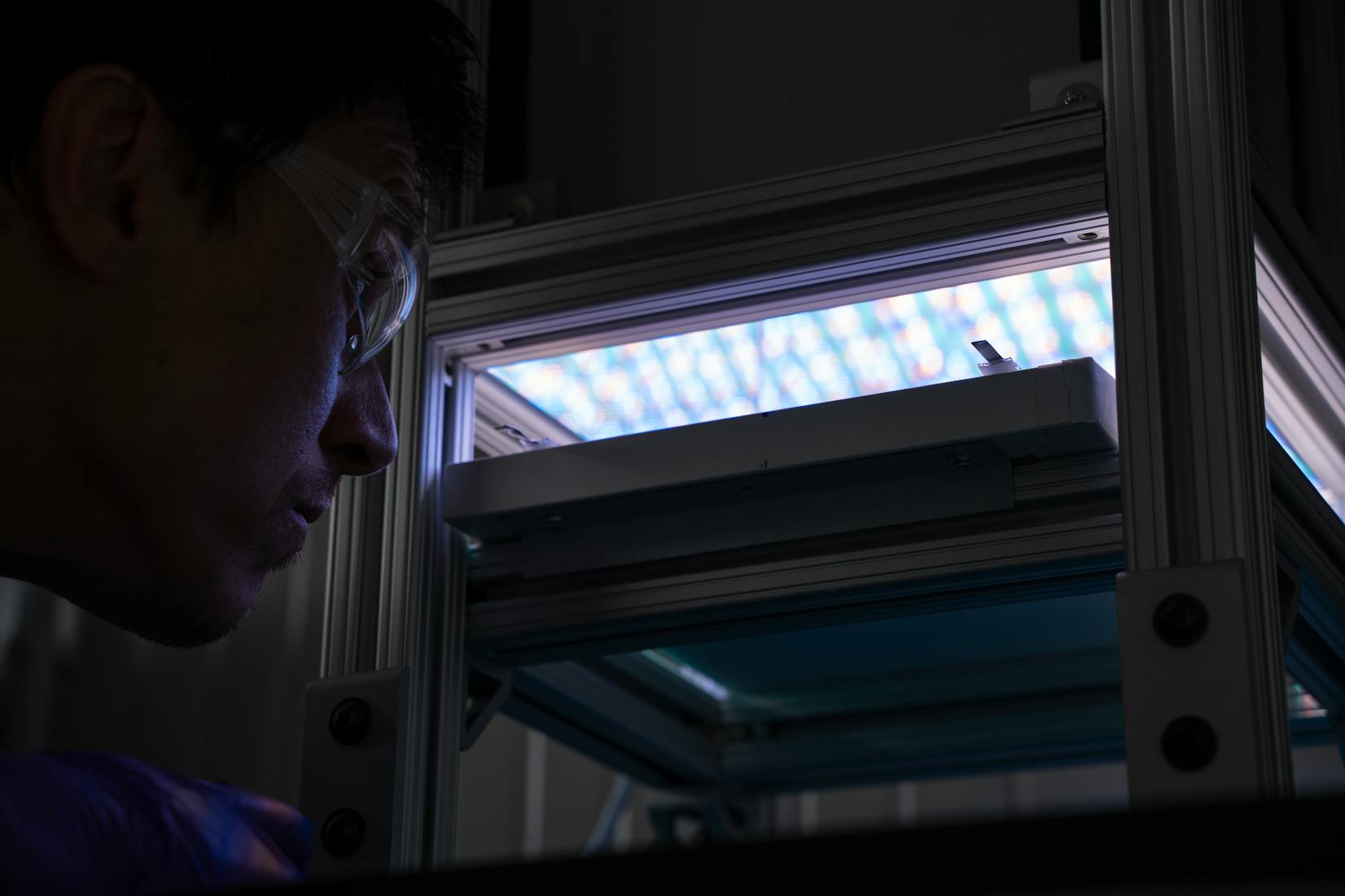

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De GiovanniOnce the modules are “baked,” researchers at the Renewable Energy Institute test their functionality and reliability. In particular, the current-voltage tester , surmounted by a sun simulator, measures the efficiency with which the module converts sunlight into electricity. Inside this sun simulator, the radiation emitted by numerous differently colored LEDs is fused into a whitish beam of light that mimics that of the sun.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De GiovanniIn the climate chamber, the modules are also exposed to extreme temperatures, as well as different percentages of humidity. In this way, the PV devices’ resistance to the environmental conditions they might encounter outdoors later is tested.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

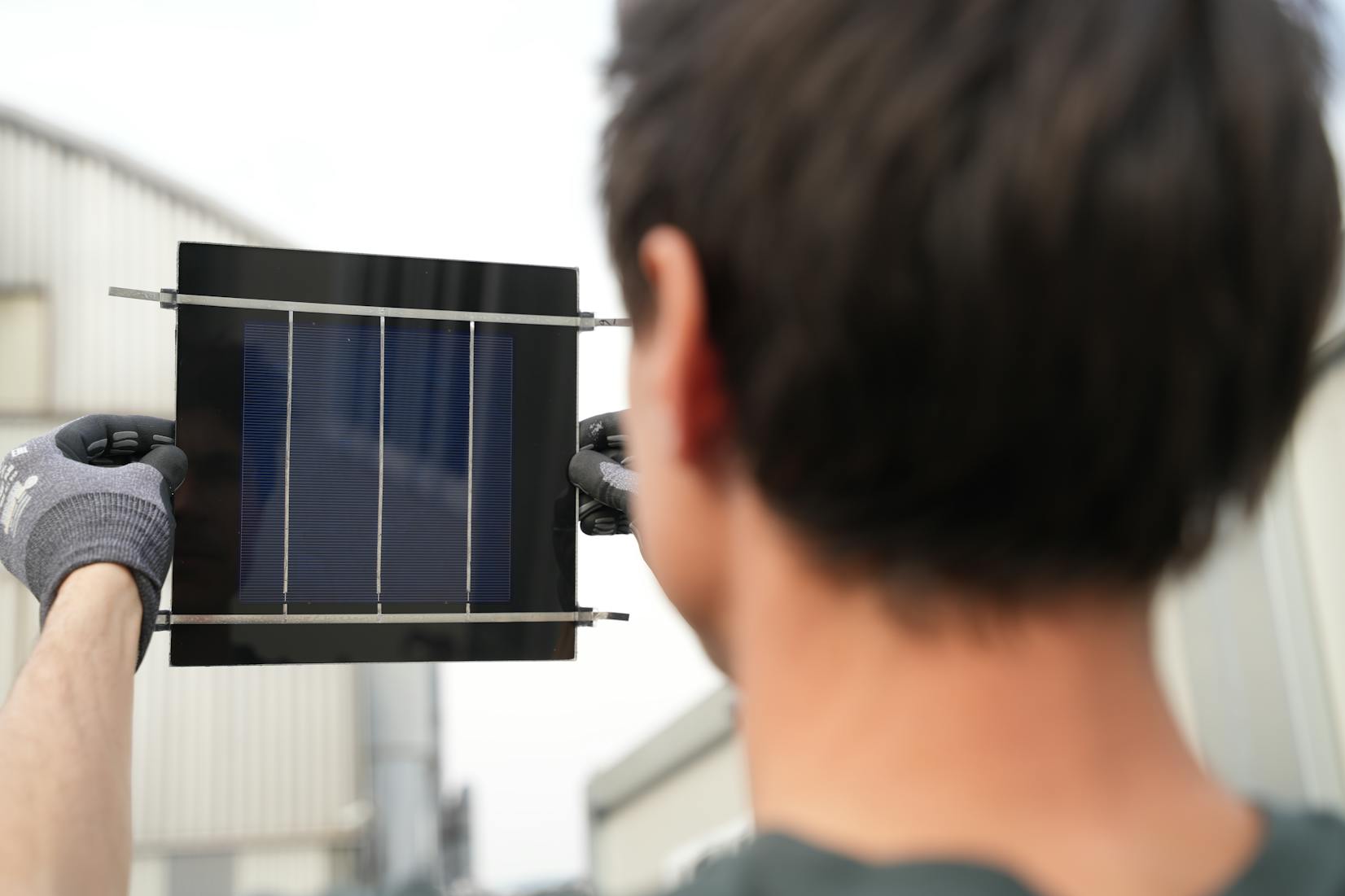

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De GiovanniThe latest step carried out at the photovoltaic prototyping laboratory is to test the “newly baked” photovoltaic modules in the Institute for Renewable Energy’s open-air area.

Credit: Eurac Research | Ivo Corrà

Credit: Eurac Research | Ivo Corrà“At our facility, photovoltaic module manufacturers can test the changes they would like to introduce in their products and measure their effectiveness,” explains David Moser, head of Eurac Research’s photovoltaics research group. “The new lab is an infrastructure that not only connects research and business but also companies that produce different components and that can test their effectiveness at Eurac Research by bundling them into a single photovoltaic module.” Designing, building, and testing prototype photovoltaic modules makes it possible to meet a number of special needs. “Consider agrivoltaics,” explains Gabriella Gonnella. “This sector needs panels that are installed over crops and because of this, should not completely shield solar radiation: this would hinder plant growth. In our laboratory we evaluate the optical properties of the components of photovoltaic modules, including the amount of light that manages to pass through them.” Then there is the issue of module mimicry. Sometimes, to protect the aesthetics of buildings, it is necessary to have modules that go unnoticed and do not disfigure facades or roofs. By testing different colors of glass or polymeric layers, technologies can be developed to meet this need as well.

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni

Credit: Eurac Research | Andrea De Giovanni