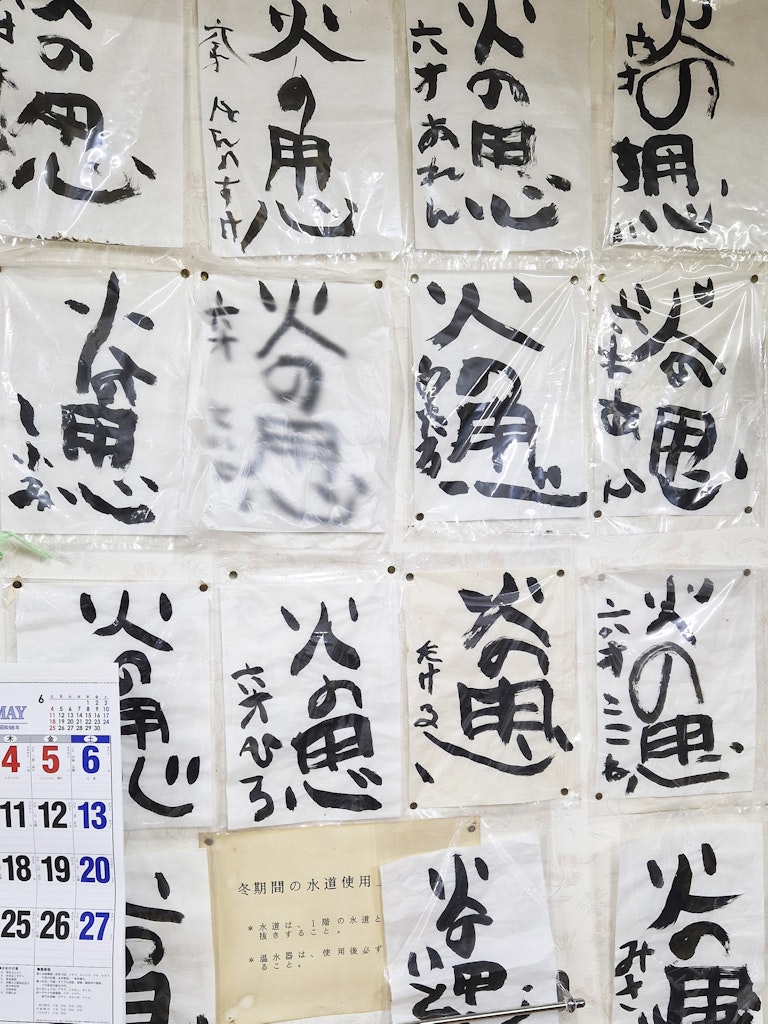

Appeasement signs that six-year-olds give to relatives and friends to avert disasters

Photo: Paola Fontanella Pisa | Eurac Research

magazine_ Article

Ready for the worst

A look at the practices, customs and rituals a Japanese community employs to protect from the risk of natural hazards

In Tadami, northern Japan, it is a tradition that at the age of six, children give relatives and friends a handwritten card with wishes of a disaster-free year. An unusual wish for some perhaps, but between floods, landslides and mudslides, the people of Tadami have more experience with disasters than most. Over two months of field research, Paola Fontanella Pisa, a scholar of Asian languages, cultures and societies and the role that memory transmission plays in disaster prevention, collected the practices implemented by this small mountain community.

In 2012, shortly after the tsunami that swept through the Fukushima nuclear power plant, Sendai and the entire Sanriku coast, Paola Fontanella Pisa was already in Japan to perfect her command of the language. She was working as a volunteer in the affected areas, and locals had taken her to the edge of town to see a memorial stone that indicated the levels to which the sea had risen in the past, a warning to future generations: do not build below this level. Beneath the stone, in fact, there was only rubble. “People would say to me, that they knew, I mean, that they should have known, but that they had forgotten,” recalls Paola. “That's exactly where the inspiration for my research came from: if people are aware that they live in places where disasters could happen and there is risk and therefore specific knowledge, then why don’t the communities at risk apply that knowledge?”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in East Asian languages, Paola earned her master’s degree in World Heritage Studies in Germany and interned at UNESCO in Paris, taking an interest in biosphere reserves. That is the study of areas where the conservation of natural resources is intertwined with community cultural values. Upon arriving at GLOMOS, Paola became interested in mountain safeguarding and the idea to start a project was born. She wanted to do a project in a disaster-prone mountainous region, possibly a Unesco biosphere reserve and picked Tadami a village in the Fukushima prefecture because it combines all these characteristics. She was aided in her choice by the Tohoku University in Sendai where she is completing her PhD. In Tadami, Paola lived in close contact with the community, hosted by a family of four generations: from 2 to 87 years old, ten of them under one roof.

After just a few days in Tadami everyone knew her. The village consists of several hamlets, in total about 4,000 people live there. You can get there in six to seven hours by train from Tokyo. Many of the inhabitants are elderly. “ I had never talked to so many people over the age of ninety in such a short amount of time,” she smiles remembering her time there. Tadami’s community is made up of rice and tomato farmers on the valley floor and people ̶ fewer and fewer now, mostly elderly ̶ who work in the mountains: gathering wild herbs and working with wood to create handicrafts such as baskets or textiles. In Tadami there is a very old tradition of using mountain resources and managing the land for agriculture as well: a perfect case study for understanding how the community relates to its surroundings.

Satoyama: the relationship with the mountain

The Japanese have a term to express this condition of coexistence and interdependence with the mountainous terrain: satoyama, the union of the word sato (village) and yama (mountain). In Japan, mountains are very steep, have dense vegetation, and can collapse in monsoon season. They provide basic services for lowland life, such as water to irrigate rice paddies and wood to build houses, but at the same time they are not very accessible and this instills a kind of awe, a kind of respect. In satoyama there are nature deities who mark the distinction between the human realm of the village and the divine realm of the mountain over which human beings have no power. People still access the mountain to gather herbs or wood, but they do so by observing certain practices: they clean the shrine of the goddess yama no kamisama, which demarcates access to the mountain, make an offering, recite prayers. In the past, the language adopted once people entered the mountains would be spoken carefully in a specific dialect to please yama no kamisama. Through these rituals, locals express gratitude to the mountain for the resources it offers and simultaneously become aware that they are entering difficult territory for which they rely on the deity for protection.

“I asked the people of Tadami what meaning they gave to these practices today, they called them ‘preparations of the heart’ or in Japanese: kokoro no junbi.” explains Fontanella Pisa. "They are practices that originated when there were no early warning systems, cell phones or other disaster management measures, even scientific knowledge was scarce, so people who went to the mountains thought 'Will I get out of this?' At GLOMOS we do a lot of work on specific hazards and continue to investigate the unique characteristics of people living in mountain areas."

The mountain goddess

In Tadami, yama no kamisama, the mountain goddess, is a very ugly woman who is envious of other women’s beauty. In the past, for fear that their presence would trigger disasters, women were not allowed to go to the mountains. During the Snow Festival, yama no kamisama is asked for a good harvest and protection from the disasters that could harm it. “I found it curious that this ceremony takes place in winter and not at the start of the agricultural season, then I understood how the rhythms of nature work in Tadami. For six months of the year the farmers work tirelessly in the fields, during the other six, they can’t do much because of snow that reaches up to four meters. This is the time when they engage in handicrafts or processing local rice products, such as alcohol or puffed rice snacks, and have more time to be together and entertain themselves,” says Paola.

In recent years, however, snowfall has also decreased in Tadami. “It didn't seem real to the farmers! If the snow melts earlier they don’t have to hurry to prepare the fields for planting and clean the irrigation canals that fill up with mud, grass, everything in winter... I know because I helped clean them too and while I was shoveling, I was asking questions,” laughs Paola. The downside is that with less snow, there may not be enough meltwater to grow rice. “I had scheduled an interview with a farmer who canceled it at the last minute. His reasoning was that it was finally raining, and that he needed to take advantage to plow the field while there was water. With that he drove off with the tractor in the rain.”

Everyone knows each other, everyone knows how to help

In Tadami, rain, monsoons and typhoons have caused a lot of damage in the past. A few months after the 2011 tsunami, there was a major flood. As a result, the Tagokura Dam, built at the entrance to the village after World War II, was in danger of collapsing and because of this, the company that operated the hydroelectric power plant, decided to open all the emergency floodgates and release a huge amount of water into the river which then overflowed. There was no alternative, but the damage was incalculable; the rail network was disrupted for the next ten years. “The mayor at the time told me that helicopters had been sent to evacuate the inhabitants of a small village that was completely isolated, without water and power, but they refused to leave. They stayed because at the community level they were equipped to handle the situation. They had, and still have, warehouses with very thick walls and a system of doors that allow them to keep all the valuable things safe: crops, pickled vegetables, mattresses and bedding,” Paola explains.

In Tadami, everyone knows each other and knows they can count on each other. They know where each elderly person lives or if there is someone in particular need of help. They have a very strong sense of collective responsibility. For example, twice a year they all clean the irrigation canals of the rice fields together. This is done by those who have sold their fields to a farm and now work there as employees, but also by those who don’t work there at all. “One wonders why, since then the harvest does not go to them,” reflects Paola. “The reason is that this activity is done collectively to raise awareness of disaster management.” These irrigation canals are the same ones that run from house to house and that people draw from in case of fire, in Tadami, the houses are wooden and heated with a stove. However, the canals also serve to regulate the flow of water during heavy rains and prevent flooding. The community gets together to clean up because they share responsibility for the safety of the village. “They are aware of the risks that can occur and know how to deal with them. When I asked questions about disaster prevention, they knew their answers. For example, they all told me proudly about suigen no mori, that the nearby beech forests have thin and deep roots which gives them a unique ability to retain water. This makes them valuable for agriculture, but also in disaster prevention because they prevent landslides and mudslides. It was very interesting for me to see how this was widespread knowledge.”

It's never too early for prevention

Disaster awareness is formed from an early age in Tadami where it is a tradition for children who turn six to hand out to family and friends a piece of paper with the inscription hi no youjin “beware of fire” as a wish that disasters do not affect their loved ones. In the past, this custom was created to protect against fires; today the risk of fire is less frequent, but the tradition has remained extending to disasters in general. “In Tadami, not only in every home, but also in stores, bars, restaurants and even in the small supermarket these propitiatory signs are hung. Six-year-olds write them because in Japanese writing the kanji, that is, the characters, can be read in different ways, and rokusai (meaning six-year-old child) can also be read musai (meaning without disaster). Because of this dual reading, the age of six is considered propitiatory for the prevention of disasters. After some time seeing those signs, I could recognize the writing and guess who had written them,” laughs Paola.

Different concerns, different visions

Collecting all these traditions, experiences, and knowledge and then giving them back to the community so that they can be integrated into climate change adaptation processes is the goal of the GLOMOS project in Tadami. Through a series of workshops organized with the support of researchers from Osaka University and Newcastle University, Paola gathered the experiences of the people to create a spatiotemporal map of the disasters that have affected the village. The villagers then listed the management and adaptation practices to climate change that they know of, specifying the administrative level they are implemented. “The communities were the ones who defined them: from the national level to the province, prefecture, village ... down to the individual. My goal was to involve the people and create the workshop together, work on the issues that are priorities for them. There was a lot of participation, more than I expected. For my part, I tried not to weigh too heavily on the little free time the farmers have and organized a time that could be enjoyable for them. One evening, after work in the fields, I brought food and drink. We had dinner together outdoors and used a van to hang posters and post-it notes on,” she recalls.

Now it’s a matter of analyzing all the information to understand how disaster management and prevention practices interact with each other and in relation to the territory and the needs of the population. Something has already emerged. During the workshop in the fields, one of the farmers expressed concern about the national government’s proposal to use paddy fields as a flood buffer. “For a farmer, to lose the crop is equivalent to losing everything. When you talk about disaster you also have to specify in relation to what and for whom. The authorities, who have a responsibility to the people, have priorities that do not always match those of farmers concerned about their livelihoods. If Tadami no longer offered a livelihood, people would be forced to move to the city. Complex dynamics come into play that are compounded by a reliance on technological progress, the rarity of truly disruptive events ... and perhaps this prompts compromises,” Fontanella Pisa reflects, thinking of the memorial stone along Japan’s east coast.