magazine_ Article

What smoking does to oral bacteria

A study shows the effects of cigarette use and what happens when you stop.

As part of the CHRIS study, a research team investigated how smoking affects the bacterial communities in our mouths. The results are clear: as cigarette consumption increases, the number of bacteria that need oxygen decreases. Furthermore, according to the results of the study – one of the largest in the world on the salivary microbiome, those who quit smoking were only indistinguishable from non-smokers after five years of no smoking.

The father of Biotechnologist Giacomo Antonello, a dentist, sometimes amazed patients with his seemingly clairvoyant diagnostic abilities: one look in their mouth and he would advise them to see a specialist, because, he explained, they might have a problem with their heart or diabetes. He often turned out to be correct. While his patients were always very impressed, for experts, the dentist’s diagnoses were justified: empirical studies show that there is often a connection between periodontitis and various cardiovascular diseases, even if the exact mechanisms are not fully understood. Giacomo, who is currently conducting research for his PhD at the Institute of Biomedicine, has now just completed a study with colleagues at the Eurac Research Institute for Biomedicine that points to one possible factor: in people who smoke, the alteration of the healthy community of oral bacteria could contribute to the increased risk of these diseases.

The study, which was conducted as part of the CHRIS study in Val Venosta, asks two central questions: What exactly happens to the bacterial community in the mouth, the so-called oral microbiome, when we smoke? And what effect does quitting have on these same communities? To find out, the research team in Bolzano, together with epidemiologist Betsy Foxman from the University of Michigan, analyzed saliva samples from more than 1600 people – a huge number of subjects for this research field, as bioinformatician Christian Fuchsberger, Giacomo’s doctoral advisor, emphasizes: “There are hardly any large studies on the salivary microbiome. This is a young research field in which a lot is happening right now and one in which not everything is conducted so clearly. Many of the current studies are working with very small numbers of cases, for example, which means their results are not broadly applicable.”

Photo: Silke De Vivo | Eurac Research

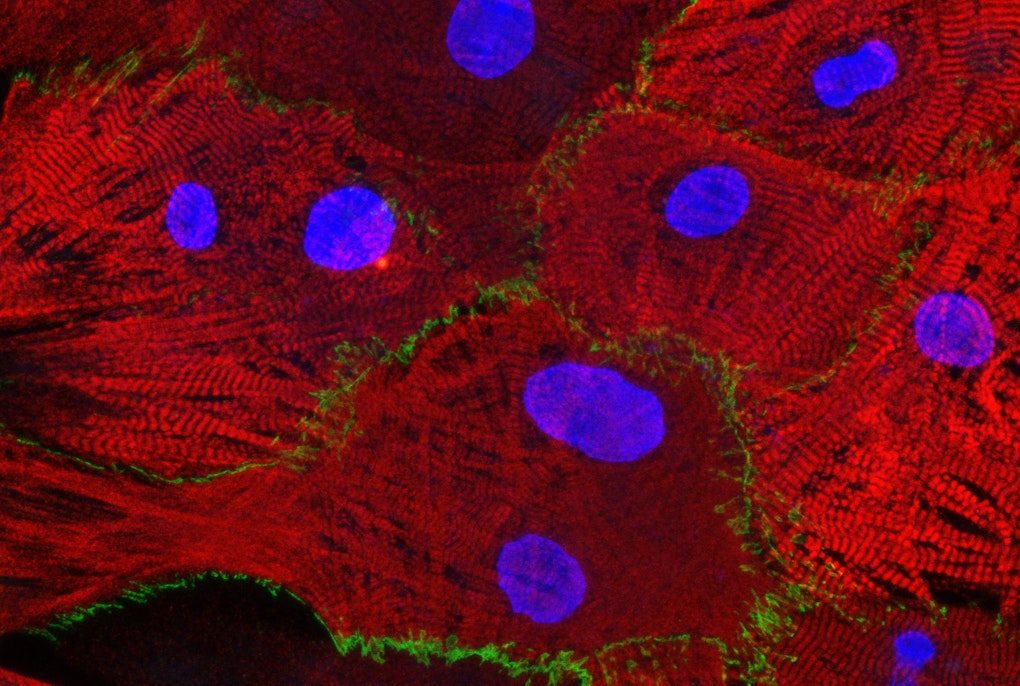

Photo: Silke De Vivo | Eurac ResearchMicrobiome research is a fairly young field: just a few decades ago, the communities of trillions of microorganisms that live on and in humans – mostly in the digestive tract – were considered of little significance by scientists. Now, the microbiome is taking center stage and is recognized to be of massive importance to our development and health. The intestinal microbiome is the subject of intensive research with a major study currently underway at the Institute of Biomedicine (see box). Compared to the microbial density of the intestine, where thousands of strains of different bacteria live, our mouth is only sparsely populated. However, saliva has a particular advantage for studies: it is relatively easy to sample. Researchers can therefore acquire the data they need to investigate whether it is possible to identify changes in the oral flora (biomarkers) that indicate certain diseases, which, if found, could provide a valuable diagnostic tool that healthcare systems could easily employ.

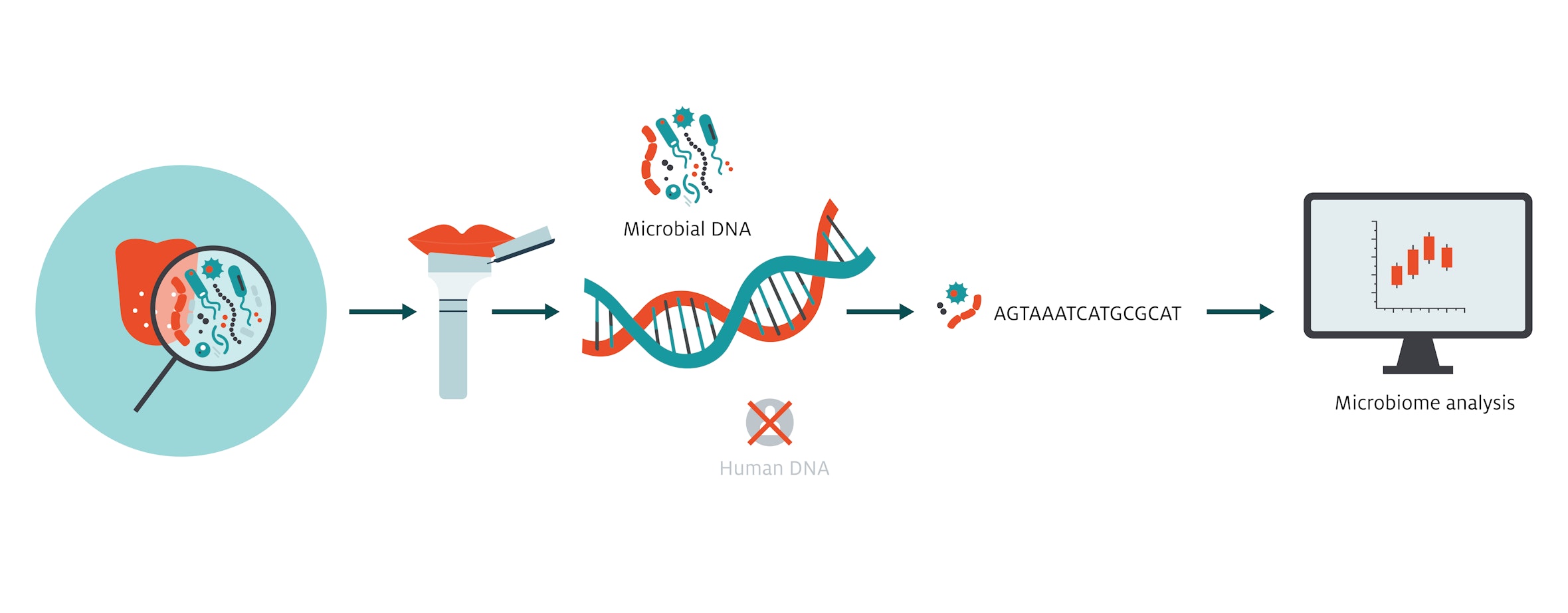

In the CHRIS Study’s examination, CHRIS participants were requested to spit 5 milliliters of saliva into a special collection tube. The participants were divided into groups according to whether they were current smokers, had stopped smoking, or had never started. Those who had quit were asked exactly when they had quit, and those who still smoked were asked about the number of cigarettes they smoked per day. To get a picture of the microbial community in each mouth – which species were represented and at what frequency – the research team employed a universally used technology for identifying bacteria, namely sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, a gene which represents something like an “identity card” for each different species.

“We have observed that the effects of smoking persist for years. So then, of course, it’s interesting to ask whether these effects are related to certain diseases.

Christian Fuchsberger

Giacomo’s research using the microbiome data collected in the CHRIS Study showed clear results. People who have never smoked carry a significantly different microbial community in their mouths than people who still smoke or have recently given up. Cigarette consumption primarily affects the bacteria that need oxygen:aerobic bacteria. The number of these bacteria decreases continuously the more cigarettes one smokes; if one stops smoking, these aerobic bacteria gradually increase again. And the longer the smoke-free period, the more aerobic bacteria are found in the saliva. Only after five years of not smoking are former smokers indistinguishable, in terms of aerobic bacteria in their oral microbiome, from people who have never smoked. “We have observed that the effects of smoking persist for years,” Fuchsberger says. “So then, of course, it’s interesting to ask whether these effects are related to certain diseases.”

Smokers are known to have an increased risk of both periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Could the changes in the oral microbiome caused by cigarettes use play a role in this? This is where a function of the bacteria that live in the mouth comes into play, and like everything to do with our microbiome, it has been receiving increasing attention for some time – some of these bacteria, mainly aerobic ones, convert the nitrate we ingest with food into nitrite, which then become nitric oxide. Nitric oxide is an important substance for regulating blood pressure, among other things. If too little nitric oxide is available, this could contribute to poorly perfused gums and cardiovascular disease. Now, the study in the Venosta valley did not measure nitric oxide in saliva, but it did examine the microbes in it; all the research team can say, therefore, is that the more the subjects smoked, the fewer nitrate-reducing bacteria lived in their mouths. That this could be an additional explanation for why smokers have a higher risk of periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease is “a hypothesis that needs to be tested in further studies,” Giacomo emphasizes. He is already pursuing the next question based on the CHRIS samples. Namely, what are some of the other factors that influence our oral flora and to what extent? What role does genetics play, and what role do the people we share households with also play? He will only be able to answer this question in about a year’s time, but one thing is already very clear: who we live with is very important.

Microbiome research in the context of the CHRIS study

The team involved in the CHRIS microbiome study does not only research the impact of smoking on the salivary microbiome. Another major study investigates the role of gut flora in type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Evidence shows that both diseases are associated with an altered composition of the microbial community in the gut; however, the exact relationships are still unclear. To better understand them, around 350 CHRIS study participants– half of whom had type 2 diabetes – were asked to take part in further examinations; among other things, an ultrasound examination of the liver was performed.Additionally, stool and saliva samples were collected for examination of the microbiome. The results of the study, in which the research team is collaborating with the world-renowned microbiome experts Nicola Segata of the University of Trento and Herbert Tilg of the Medical University of Innsbruck, are expected in 2024.